Tonight Can We Just Get It Right

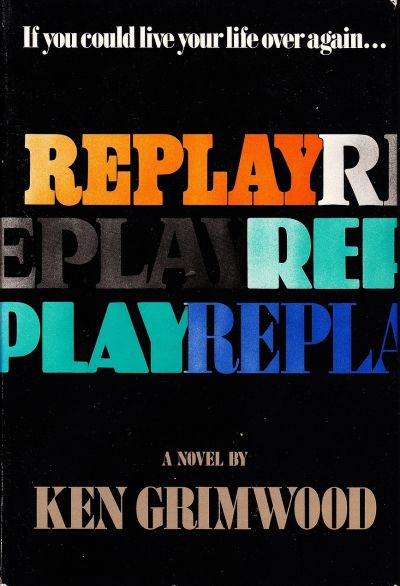

Replay

By Ken Grimwood

4 Nov, 2021

Ken Grimwood’s World Fantasy Award-winning 1986 Replay is a stand-alone temporal recursion novel.

October 18, 1988: Jeff Winston is stuck in a dead-end radio job and his marriage to Linda is disintegrating. Distraction might be welcome, but what happens is unwelcome. He and his wife are in the middle of a painful discussion of divorce when Jeff has a massive and painful heart attack. Jeff dies, ending the marriage in an unsatisfactory way (from Jeff’s POV).

But … Jeff suddenly finds himself alive and well again. As a young Jeff, a college student in 1963.

Once he convinces himself that this is reality, not a dream or hallucination, Jeff sets out to avoid the mistakes of his first life. Having rather conveniently memorized the outcome of many major sporting events, it is easy for young Jeff to amass a small fortune. Jeff then uses his knowledge of the stock market futures to turn the small fortune into a large fortune. The life that follows is very nearly perfect save for one minor detail: when October 18, 1988, rolls around again, Jeff succumbs to a fatal heart attack.

Jeff wakes again in 1963, although several hours later than he did the first time he was resurrected. All of the progress he made in his second recapitulation has vanished, including his daughter Gretchen. While he can recreate his fortune, Gretchen has been irretrievably erased.

October 18, 1988, is seemingly fixed as Jeff’s death date. However, he can alter what he does between the date he revives and Oct 18, 1988. No matter how awful his decisions turn out, he can be assured of a do-over once that fatal day arrives. Therefore, he can explore many lifepaths, with the catch that all of his progress will be erased in 1988.

During one recursion, he is astounded to see an unfamiliar 1974 blockbuster film, drawing on the skills of Spielberg and Lucas (then obscure). Investigation proves that the film’s creator, Pamela Phillips, is a replayer like Jeff, limited to living a similar (but slightly different) period of time over and over. Now at least they have company. It’s convenient that they quickly fall in love.

Three questions confront them: are there other replayers? How best can they use their peculiar circumstances to optimize history? And most importantly: given that each cycle is shorter than the previous one, what happens when the cycles reach zero duration? Final death or an eternity of dying?

~oOo~

For reasons that are obscure — OK, because this was written before John D. MacDonald died — Jeff has access in most histories1 to more Travis McGee novels than we do, which means Jeff finds out what happens after McGee discovers he has a daughter in Lonely Silver Rain. Well, it matters to me.

The first question I expect new readers will have on encountering this for the first time is: is the plot derivative of Richard C. Lupoff’s 1973 “12:01 PM,” which also involves a time loop and in one iteration, a fatal heart attack? Lupoff’s story involves a much shorter span of time, constraining its protagonist’s possible courses of action. As well, Lupoff provides an explanation, whereas Grimwood, the author of this novel, did not2.

As far as I recall, this is an unusual example of this sort of time travel novel, in that ultimately the protagonist’s efforts to overwrite history with an improved version come to nothing. Not because progress is futile due to inherently flawed human nature, although there might be a little of that, but because the nature of temporal recursion. Once the cycles shorten to zero duration, the replayers can no longer alter history, and it returns to the course it was on before the phenomenon began3.

The lesson Jeff takes away from his experience is that one should learn to appreciate the moment in hand rather than obsess about perfect outcomes. Whether that was the point of the exercise and indeed if there was even a point is unclear, but that’s Jeff’s take on what may have been centuries of replays. There are probably worse lessons to learn.

Grimwood’s prose and characterization are functional but not noteworthy. It’s possible he had some deeper intent than I could find in this book; if so, perhaps the sequel on which he was working when he dies would have revealed it.

Ken Grimwood died in 2003, at comparatively young age (59) for a pre-Dystopic American. If he got his own replay, it’s possible that he completed the sequel in a continuity none of us will remember.

Replay is available here (Amazon US), here (Amazon Canada), here (Amazon UK), here (Barnes & Noble), here (Book Depository), and here (Chapters-Indigo).

1: With the possible exception of the Maximum American Dystopia Jeff and Pamela create during one cycle, after they decide it would be an incredibly good idea to reveal to Cold War America that they have an idea what history has in store, Or at least they do until the CIA starts using the information they extract from the pair to fix things.

2: Assuming we discount the explanation provided by a third replayer, that Aliens Did It, on the grounds that the replayer is a deranged serial killer.

3: Began for Jeff. As one could deduce from there being three replayers, the looping is not peculiar to one span of history. Other people experience the same effect at later periods, and presumably were doing so before it was Jeff’s turn.