Two-Fisted And Fast On Your Feet

Justice Inc.

By Aaron Allston, Steve Peterson & Michael A. Stackpole

14 Jul, 2022

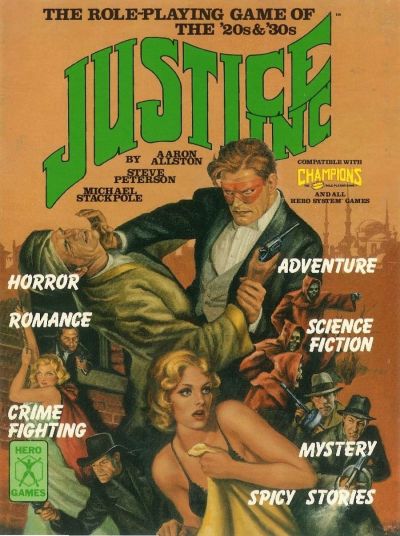

Aaron Allston, Steve Peterson, and Michael A. Stackpole’s 1984 Justice Inc. (JI to its fans) is a tabletop roleplaying game. It is based on the pulp fiction of the 1920s and 1930s.

And what did roleplayers of the long, long ago find when they opened Justice, Inc.’s attractive and sturdy box?

Modern readers might find the saddle-stitched booklets in the box a bit slender, but they met industry standards of the day. Alas, this includes the dire lack of an index, which I can assure I regretted when I was trying to hunt down the definition of skill familiarity. On that note, document organization is a bit idiosyncratic. For example, the rules mention skill familiarity before actually defining it.

The rules also causally shift between metric and imperial as comfortably as might any Canadian of a certain age. This would be only a minor quirk except, as this game belongs to the generation of games in which miniatures and hexmaps were assumed to play a role, the term “inch” has a specific meaning in the game (one game inch represents two metres1 on a hexmap), and is cited frequently in the rules. Reverting to imperial in other contexts invites confusion.

Also in keeping with the standards of the time: the art is of variable quality, as is the kerning. And … the text appears to assume that players and their player characters will be men, with women relegated to supporting roles consisting mainly of being rescued. It’s interesting that the adventures provided don’t seem to make the same assumption. I note that 1989’s Champions 4thedition by the same publisher had what may be a pertinent disclaimer:

For our convenience, we have employed the male gender throughout this product. This does not imply any chauvinism on our part (quite the contrary), but it is hard to say him/her/it, or he/she (or “s/he”) every time the situation crops up. So, please accept our apologies for this shortcut.

In a process analogous to Chaosium’s adaptation of the RuneQuest rules to the Basic Roleplaying System used in a wide variety of RPGs, publisher Hero Games set out to retrofit the core essentials of their superhero roleplaying game Championsto a more universal system, which they dubbed the Hero System. JI was their second attempt2 at this, following 1983’s Espionage!3

Given that just about any sort of character could potentially appear in a superhero comic, one cannot fault their logic: a system that could handle superheroes should be able to handle all characters and genres. Like Champions, character design is choice-based rather than random. Players expend points to acquire characteristics, skills, and abilities. This ruleset offered more flexibility and choice than many other RPGs of the time.

Judicious selection of skills, psychic powers, and weird talents, in concert with individual character concepts and (of course) actual roleplaying, combined to generate a variety of characters. Quite a variety, actually.

JI wasn’t a bestseller, due to two problems:

- A near-total lack of support: the entire line consisted of this box set, the adventure Trail of the Gold Spike, and the source book Lands of Mystery, both of which were written by the talented Aaron Allston.

- The fact that Chaosium’s Call of Cthulhu (CoC) appeared first and, despite a very specific horror focus, managed to establish itself as the go-to pulp-era roleplaying game. Of course, CoC was well-supported, which points to the first issue again.

Having played in a number of homegrown JI campaigns, I can attest that the system was very flexible and could handle many genre settings. It is a shame that it didn’t flourish.

Astonishingly for a thirty-eight-year-old tabletop game that was never particularly well supported, Justice Inc. is still in print and may be purchased here, at least in affordably priced PDF format. Acquisition of physical copies will require used bookstore and online searches.

1: An incredibly vulgar joke goes here.

2: Oddly, JI mentions Hero Games’ Danger International (DI) as though it preceded JI. DI did not appear until 1985, a year after JI hit game stores.

3: Espionage! is the one 1980s Hero product I did not own, because it was so hideous looking.

And now for the nitty-gritty on the contents:

Core Rulebook:

Foreword by Hugh B. Cave

Cave was a popular pulp writer with whose work I am not familiar. The foreword makes it clear the game didn’t aim at subtle nuance: this is a game in which the heroes are very good and the villains extremely villainous.

Character creation

The thirty-seven-page character creation section outlines the steps required to create a player-character. It’s like the Champions game in that players are provided with a limited number of points with which to purchase characteristics, skills, powers, and talents. More points can be acquired by taking on disadvantages or defaulting to one of the package deals offered.

Characteristics

JI has eight primary characteristics (strength, dexterity, constitution, body, intelligence, ego, presence, and comeliness) and six “figured” characteristics whose base value is derived from (or “figured” from) various primary characteristics (physical defense, energy defense, speed, recovery, endurance, and stun). The cost to purchase characteristic points varied by characteristic, apparently driven by how useful the characteristic was in play.

There were also three combat values:

- offensive combat value (derived from dexterity)

- defensive combat value (derived from dexterity)

- ego combat value, derived from ego

Due to a few mathematical quirks in the system, certain values for primary characteristics were the most cost effective and therefore very commonly selected by players. Characteristics above 10 and evenly divisible by 5 and ones ending in 3 or 8 were most common, so that while in theory primary characteristics could be any value between 1 and 20, in practice one encountered a sea of 13, 15, 18, and 20s (unless the characteristic was dexterity, in which case 14 was also common). This amounted to just four (or five, for dex) of twenty possible options.

Skills

Exactly what it says on the tin. JI provided far more skills than any player could afford to purchase. In theory character skill sets could easily be unique; in practice, I noticed that players weren’t all that adventurous in chargen.

Psychic Powers

These are supernatural powers some characters might possess in certain kinds of campaigns. All are passive: sensory powers that allow the characters to perceive the world around them in unconventional but useful ways. Active abilities like telekinesis are explicitly ruled out as potentially game-breaking. Additionally, psychic powers are very expensive; psychic characters will probably only have one or two abilities and will be comparatively incompetent otherwise, due to point limitations.

Weird Talents

Useful unconventional knacks, priced according to their likely utility. Of particular note as a detail suggesting the era in which the rules were written, this passage under the talent Lightning Calculator:

A player whose character is a Lightning Calculator can keep a pocket calculator or sliderule with him and use it when his character is performing mathematical functions.

Emphasis mine. 1984 seems a bit late for sliderules but of course the game designers of this era were generally old enough that their educations predated cheap electronic calculators.

Package Deals

Predesigned career paths that offered point reductions in characters. These would be far more useful if there were more than three choices (reporter, cop, g‑man) available.

Character Disadvantages

Hero allowed players to acquire more points with which to design their characters by accepting drawbacks that would frequently feature in adventures (disadvantages that never impede characters are worthless). They are more or less the same as Champion’s disadvantages. Some superhero specific options are missing. Also, this being a lower-point-total game, one gets fewer points for most disadvantages, although there are exceptions: being unlucky garners as many points in JI as in Champions.

Combat

Forty-two pages explaining Hero System’s detailed combat system, which probably deserves more word count than I will give it. Of particular note: the combination of comparative character fragility with the ubiquity of firearms (which do lethal rather than critical or serious damage) and explosives means that combat is often an opportunity to revisit chargen.

There are lavishly detailed lists of weapons. In retrospect I am struck by how little variation there is between the weapons: pistols, for example, do between 1d6‑1 to 1d6+1 damage. The names seem to be just colour. Surely even gun fanciers cannot possibly care about this sort of minutiae?

The Campaign Book

This eighty-page volumes, wrapped in a cover featuring well-known actors and fictional character I’d really have expected to be under trade mark or copyrighted, provides advice on running campaigns in general, and in the specific genres of crimefighting, espionage, action, horror and occult adventure, detective, mystery adventure, spicy stories, science fiction, and western adventure. Campaigns can be run in more than one genre at once.

The volume provides such setting resources as a timeline for the eras and the Empire Club, a social organization where adventurers can socialize with like-minded colleagues and potential patrons.

In addition to a solo adventure intended to familiarize players with the game mechanics, there are three sample adventures:

- The Coates Shambler (a supernatural mystery… or is it a purely mundane attempted murder?)

- The Gray Scarecrow (a western mystery)

- Killer Candy (a mystery taking place in the Empire Club itself)

Also included in the box: three six-sided dice, and a catalog which from the perspective of 2022 reeks of pure nostalgia.