Welcome to the Jungle

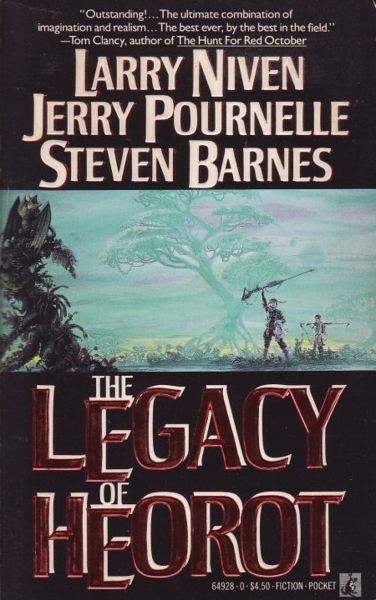

The Legacy of Heorot (Avalon, volume 1)

By Larry Niven, Jerry Pournelle & Steven Barnes

24 Jun, 2021

1987’s The Legacy of Heorot is the first volume in Larry Niven, Jerry Pournelle, and Steven Barnes’ Avalon series.

A century after being meticulously selected to establish Man’s first colony on an extrasolar planet, the settlers aboard the National Geographic Society’s starship Geographic establish a foothold on the Tau Ceti IV planet of Avalon. Prudently selecting an island for their settlement, they begin the task of transforming the island into an ecosystem in which humans can thrive.

Despite the unpleasant surprise that a century of hibernation has a cognitive cost apparently undetectable over shorter timespans, the settlers have thus far been successful in their bid to make Man’s Manifest Destiny IN SPAAACE a reality. Indeed, they’ve been so successful that ex-soldier turned security expert Cadmann Weyland seems superfluous to needs.

The settlers are overconfident. Cadmann is crucial to the colony’s survival — or he will be if he survives the calamity bearing down on the naïve colony.

The settlers had noticed the island’s curiously depleted ecosystem, a lack which some feel suggests that there was a mass extinction event some time in the geologically recent past. Thus far, however, they have not had time for the comprehensive survey needed to determine what happened. The culprit soon makes itself obvious.

The island’s rivers conceal an apex predator as smart as a gorilla, armed with keen senses and formidable natural weapons, and capable of bursts of enhanced speed and strength. The first predator to notice the humans begins by picking off domesticated animals. The colonists dismiss this as dog attacks (by the imported dogs). Cadmann insists that there’s a threat, which leads the oblivious colonists to speculate that Cadmann himself is staging the attacks to justify his cushy job.

Cadmann is vindicated when one of the creatures concludes that nothing in the Terran colony is a threat and openly attacks the colony. Thirteen colonists die and the colony infrastructure is badly damaged before the settlers can pour enough firepower into the beast to bring it down. It’s a horrible revelation, but at least the threat is plain. Or so the colonists think.

Determined to make the island safe, the settlers carry out a methodical extermination campaign, tracking down and killing every grendel on the island. It’s a stunningly successfully effort. Too bad that that humans don’t understand the grendel life cycle. They’ve eliminated the adult grendels, unaware that the adults prevent most juveniles from maturing into adults. Consequently, new adults will soon begin emerging from the island’s rivers in unprecedented numbers.

The primary non-grendel source of meat available to this horde of ravenous predators? The occupants of the human colony….

~oOo~

The National Geographic Society1 managed to dispatch Geographicto Tau Ceti, which implies this is the sort of effort a subnational group can afford in the pampered, rich, overpopulated world of tomorrow2. Yet at the same time proxmires have prevented any follow-up. This seems inconsistent, although it does serves the plot purpose of convincing the colonists that their survival is politically important. If they succeed, Earth may found more extrasolar colonies.

The authors stumbled across an explanation that justifies any number of bad decisions: hibernation instability AKA cognitive freezer burn. While not every colonist has noticeable brain damage, it’s reasonable to assume they may all have some degree of damage thanks to that century spent on ice. Consequently, it’s not surprising that from time to time the humans make unfortunate choices.

The authors also provide one of the few in-story justifications for conservation of ninjitsu that I recall. When they are young, grendel are individually weak but they make up for this with numbers. Very few grendels survive to adulthood but those that do are experienced and huge. Thus, having set the stage for an ecological calamity, the humans first face Zerg rushes of hordes of weaklings before their foes progressively level up while becoming less numerous. It seems like a no-brainer to adapt Heorot to a video game, but I am unaware of any such adaptation.

The person who requested this also requested discussion of the similarities and differences between this and Sue Burke’s 2018’s Semiosis. Like Legacy of Heorot, Semiosisinvolves the attempt by a small group of humans to settle an unfamiliar world despite the colonists’ lack of numbers, inability to summon reinforcements from Earth and a comprehensive ignorance of the ecosystem into which they are trying to insert themselves. Whereas the characters in Heorot are fairly standard elite colonists of the sort seen in many, many SF novels, the settlers in Semiosis might be described as annoying hippies. Heorot’s settlers have the further advantage that they’re dealing with an overt threat easily understood, whereas the nature of the challenge in Semiosis is more subtle and easier to overlook, particularly if one hasn’t brought along a crack team of scientists or the equipment they need.

Given the differences, it’s not terribly surprising that by the end of their respective novels, the humans on Heorot have prevailed at least for the moment, whereas the humans in Semiosis are well on the way to being domesticated3by the dominant lifeforms on their world. Given that humans only barely managed to make an Avalonian island theirs despite the advantage that islands tend to have simpler ecosystems, a betting person might give the Semiosissettlers better odds for long term survival. At least elements of the local ecosystem will be trying to keep them alive.

One could also compare and contrast Heorot and Robinson’s wretched Aurora, whose settlers are not just incredibly ignorant of their target world but also uncurious and very easily deterred. For that matter, Heorot is the mirror image of David Gerrold’s Chtorr series: instead of being colonized by a poorly understood alien ecosystem, humans are trying to insert themselves into one,

Unsurprisingly, this novel plays with many of the tropes that the savvy reader will expect from Niven and Pournelle. Niven: the book reads a bit like someone got a cool idea after reading a pop sci article. Pournelle: women cheerfully accepting the need for polygamy and focus on producing numerous kids. Barnes’ contribution: the book is actually readable, unlike other late 1980s books by Niven and Pournelle.

If you want read a novel about an escalating series of battles between humans and implacable alien foes, this delivers. If that’s not what you’re looking for, look elsewhere. Heorot is very clear in what it is about.

My copy is an aged Pocket Book edition.

1: The colonists arrive with the intention and tools to introduce terrestrial ecosystems to Avalon in the name of Manifest Destiny. However the National Geographic Society might feel about conservation on Earth, it’s OK with terraforming other worlds. Which seems a bit odd, but there is no novel here if the funding body for interstellar colonization feels interstellar colonization is unethical and should not be funded.

2: Which raises the question of when this novel is set. The film The Wizard of Oz (1939) is said to be two hundred years old. That would place this sometime around 2139, which in turn means Geographic was dispatched some time around 2039. Well, at the time of writing 2039 was as far in the future as 2073 is to us.

3: Nobody suggests trying to domesticate grendels, although humans being humans it seems inevitable that someone will not only propose it but attempt it. Perhaps this occurs in the later novels, which I have not read. If it works, humans would have a partner of inestimable value in extending human control of the planet but it seems as likely to work out well as domesticating hippos or salt water crocodiles.