Words You’re Gonna Regret

Night of Power

By Spider Robinson

17 Sep, 2024

Spider Robinson’s 1985 Night of Power is a mercifully stand-alone near-future race war novel.

Aging dancer Dene Grant can hardly turn down an offer to dance at the Joyce Theatre. She, her husband Russell, and Russell’s their thirteen-year-old mixed-race daughter from a previous marriage Jennifer make the trip from Halifax, Nova Scotia1 to New York City, center of American publishing, finance, and simmering interracial conflict about to boil over.

Scarcely has the family entered New York City when a gang of African American youth criminals descends on them with robbery, murder, and worse in mind.

The Grants’ protestations that they are Canadian do not dissuade the violent youths. The fact that Russell is white and Dene black inflames their ire. The Grants survive thanks to the intervention of saintly Michael2, who admonishes the youths and escorts the Grants to safety.

New York City is a city filled with crime, law-breaking, misconduct, transgressions, and rampant malefaction. There is always an element of danger for locals and visitors alike. Nevertheless, the benefits usually outweigh the risks. Usually. As it happens, the Grants have chosen a particularly bad time to visit New York and the risks are especially high.

The US has a race problem. Whites fear and oppress black people. Black people fear and resent white people. Clearly the only future ahead of the US is a terrible race war that African Americans will be compelled to start, even though it is a conflict that they will lose.

Michael believes he has a solution. A network of strategic alliances between various African American power factions combined with military expertise (courtesy of the propensity of the US to draft black men) has given Michael the means to take the entirety of Manhattan hostage. Not only will Michael’s army have millions of hostages. but also the

World Financial Center and Trade Center, the Federal Reserve — forty percent of the gold in the country — a whole lot of corporate and fiscal data bases, the machine that controls national TV, radio, and long distance phone, the finest museums in the country, and almost a million hostages including some of the richest and most powerful people in the world.

This, Michael believes, will be sufficient to force the US to surrender the prize Michael truly wants:

the states of New York and Pennsylvania evacuated and turned over to us. Two out of fifty-one states. Industry, farmland, seaport, resources — everything needed to house and feed every black person now living in America, with room to grow in for decades to come.

“I want to found a new nation on that land, of and for black people, and call it Equity.”

It’s bold scheme. Perhaps it will work. The question facing the Grants is if they will survive Michael’s attempted coup.

~oOo~

Yes, this is the novel with the crazy-glue scene. Also, the one where the white guy laments that he has no burnt cork so that he could fit in better with African Americans. Also, the one where Robinson seems to have confused Muslims with Sikhs.

The first thing that caught my eye when reading this was the acknowledgement section:

Night of Power was written with the assistance of the Canada Council for the Arts, and the Nova Scotia Department of Culture, Recreation & Fitness. Additional invaluable assistance, in the form of time, expertise, research, advice, and/or general support, was given to me by (among others): George Allanson, Susan Allison, Isaac Asimov, Stanley Asimov, Bob Atkinson, Jim Baen, John Bell, Bill and Sue Bittner, Ben Bova, Kathy and Tom Cullem, Patrick Doherty, Robert A. Heinlein, Don Hutter, Bill Jones, Jack MacRae, Kirby McCauley, Betsy Mitchell, Major H.K. O’Donnell, USMC, Fred Pohl, James V. Robinson, Charles Saunders, Richard Seaver, Fred Ward, and Eleanor Wood. My thanks go to all these individuals and institutions, as well as any I may have omitted. And of course Night of Power, like all my books, could never have existed in anything like its present form without the ongoing love, encouragement and support of my wife Jeanne and my daughter Luanna.

The Arts Council detail is a bit surprising. I wasn’t surprised that art is subsidized in Canada (it is no secret in Canada), but surprised that American-born Robinson was able to secure a grant. I’ve heard that the Council of the Arts could be pissy about Americans in general and Robinson in particular. I remember an episode in which a local con that wanted a grant to subsidize his appearance at their Disco-era con reportedly had to invite Canadian-born Jeanne instead, with Spider as the plus one, and they had to invite her in capacity as a dancer, not an SF writer.

Robinson meant well. There’s proof, in the form of extensive damning commentary and statistics pertaining to the Race Question at the beginning of chapters. While a separate but equal solution could be seen as a problematic proposal, particularly from a white dude3, it’s kilometers better than Robinson’s previous Final Solution to the American Race Problem, as seen in Robinson’s Antinomy:

McLaughlin had, of course, already told her a good deal about Civil War Two and the virtual annihilation of the American blacks, and had been surprised at how little surprised she was.

It’s possible for a work to be an improvement over previous efforts without actually being very good. Night of Power has three main issues.

First, while Michael’s plan is greatly facilitated by the fact that American communications depend on an over-centralized system, courtesy of a technological break-through that allowed a company to monopolize the field, it’s hard to believe the US would under any circumstance accede to his blackmail. Historically, the US has not looked kindly on secession efforts. A much better plan would have been for Michael to blackmail the US into giving him New Brunswick and Nova Scotia.

In Michael’s defense, the novel ends before we see the long-term consequences.

Second, Robinson’s Heinlein homages — the sophomoric debates, the regrettable sex obsession4, the lectures — grated. I know, I’ve only myself to blame for reading this.

Third, while Robinson is consciously sympathetic to Michael’s cause, the narrative toolkit he brings to the task of writing Night of Power would have been more suited to a novel like Niven and Pournelle’s The Burning City. One gets the impression that Michael is the product of the writer’s conscious mind and the regrettable ethic stereotypes found elsewhere in the novel are unexamined habit. It’s as though Archie Bunker had set out with the sincere intention of writing an inspirational novel of African American liberation.

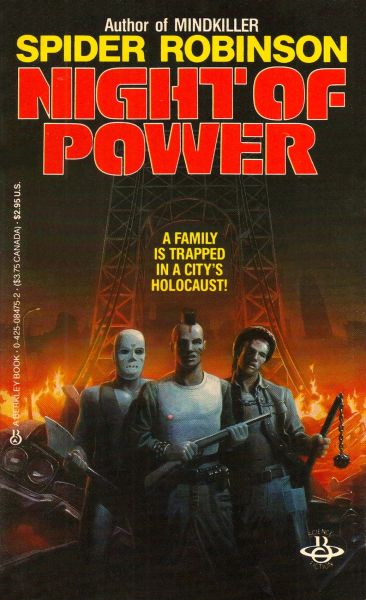

But it could have been worse! I hear some say. Surely publishers5 would have had the foresight not to offer a variety of lamentable covers for the novel, these people assert. Alas. I could tell you that was the case but I would have to lie.

Night of Power did have one legitimately interesting futuristic detail: automobiles have heads-up-map displays6.

Summary judgment: whatever its flaws in execution, the author’s motivation appears sincere. Better than Farnham’s Freehold, anyway7.

Night of Power is out of print.

1: Halifax is a Canadian city east of Yonge Street.

2: Michael is not so saintly that he won’t encourage police brutality if it targets drug pushers. Even saints have their standards.

3: Oddly, at least two other SF novels featuring black majority nations in the US were published close to the same time as Night of Power, both, I believe, written by white guys: Bisson’s Fire on Mountain (in which a successful slave revolt leads to a black nation in the south), and Callenbach’s Ecotopia (in which the West Coast’s African American population is shuffled off into their own off-stage enclave, where Callenbach would not have to think about them). Were there more? Was this a pattern I overlooked at the time?

4: There is probably a Chekov’s Gun variant for teens in Heinlein-influenced novels: the inevitability that their sexuality will become a plot point.

Speaking of Heinleinisms, in this novel the company with the near-monopoly on communications never patented their key invention lest someone use the patent to steal the technology. This succeeded because reverse-engineering is a concept so obscure I just now had to invent the term. This was, as I recall, how the Shipstone secret was kept in Heinlein’s Friday.

5: Night of Power’s publishing history is a little odd. The 1985 hardcover was from Baen, but the 1986 paperback was from Berkley. Finally, about twenty-years later, it was brought back into print by Baen. Why would Baen not have published the first MMPB edition? Or maybe the question should be why, given how many early Robinson books appeared from Berkley, did Baen publish the hardcover?

6: A display for the passenger. Robinson might have thought that a windscreen map HUD for the driver might be a fatal distraction. If so, that’s perfectly reasonable. I wonder how many wrecks have been caused by drivers glancing down at their GPS display at just the wrong moment.

7: Future publishers of Night of Power do not have permission to use “Better than Farnham’s Freehold” as a blurb.