Yesterday’s Tomorrows: the Symposium!

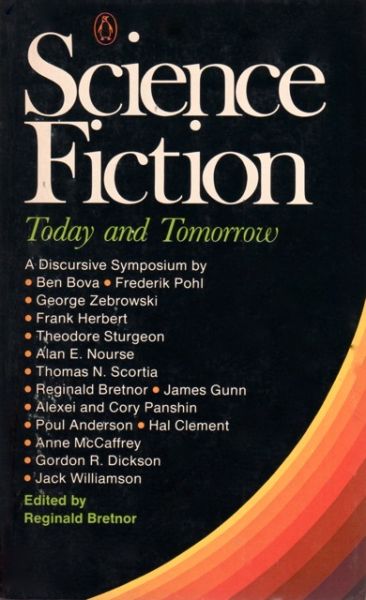

Science Fiction, Today and Tomorrow: A Discursive Symposium

By Reginald Bretnor

29 Mar, 2016

0 comments

Judging by the poll on my Livejournal, poor Reginald Bretnor is well on his way to the obscurity that awaits most of us. I remember him, not for his fiction or for the Future at War MilSF anthologies he edited (although, hrm, I do own them), but for non-fiction books like this one: 1974’s Science Fiction, Today and Tomorrow: A Discursive Symposium. He also compiled Modern Science Fiction: Its Meaning and Its Future (1953)and The Craft of Science Fiction: A Symposium on Writing Science Fiction and Science Fantasy (1976)1.

Parts of this collection provide an interesting snapshot of science fiction forty-odd years ago. Other parts, um, well .…

Introduction (Science Fiction, Today and Tomorrow) • essay by Reginald Bretnor

There are many parallels between this work and Modern Science Fiction. Bretnor recruits an entirely new list of authors, drawn from SF’s Who’s Who (many of whom cruel Time the Hunter has transformed into Who?), but the topics to which he assigns them are more or less the same topics he used in Modern Science Fiction. There is one major difference: Bretnor no longer has to justify the idea that SF is worth studying.

Science Fiction Today

The Role of Science Fiction • essay by Ben Bova

Bova explores several roles that SF can fill. Clearly the most important role is providing SF writers and fans a reason to pat themselves on the back for being slans rather than mundanes. This snobbery is something of a recurring theme in this book.

The Publishing of Science Fiction • essay by Frederik Pohl:

A historical overview of SF publishing, which leads to a discussion of the state of SF publishing in the early 1970s. Pohl is clearly aware that publishing changes from year to year. While the digital revolution is nowhere on his radar, he does raise the possibility that some transformative technology might make books (at least as they were understood in 1974) obsolete and utterly change the face of publishing. And why wouldn’t he? He had already personally experienced massive changes in the publishing industry.

Science Fiction and the Visual Media • essay by George Zebrowski

Can there be a truly SFnal movie? or are we doomed to watch monsters and mad scientists? Well, Zebrowski could not know it, but in about three years, George Lucas was going to offer a third option: brainless blockbusters.

Science Fiction, Science and Modern Man

Science Fiction and a World in Crisis • essay by Frank Herbert

What can SF offer a world faced with, for example, the certainty that

if we shared the world’s food supply with every living human being, all of us would starve.

I found this essay a wall of impenetrable Herbertian prose. MEGO. Herbert does hope that SF might grant us the flexibility to adapt to changing circumstance.

Science Fiction, Morals and Religion • essay by Theodore Sturgeon

Sturgeon sees religion and morality entwined with SF, and morality itself not as an absolute, but a work in progress.

Science Fiction and Man’s Adaptation to Change • essay by Alan E. Nourse

Whether they react positively or negatively, SF writers and fans at least admit that change is inevitable. Which is a springboard into yet another leap into Fans are Slans territory.

Science Fiction as the Imaginary Experiment • essay by Thomas N. Scortia

Scortia muses on a very specific sort of SF, extrapolative speculation.

Science Fiction in the Age of Space • essay by Reginald Bretnor

Every symposium on SF needs its Young People Need to GET! OFF! MY! LAWN! essay. This essay fills that role. Bretnor does not like hippies, the New Wave, racial agitators, or academics of the wrong kind. I particularly admire his seamless segue from denouncing irrational ivory-tower pseudoscience to endorsing General Semantics.

The Art and Science of Science Fiction

Science Fiction and the Mainstream • essay by James E. Gunn

Gunn appears to see SF as inherently different from literature, but he also seems to have actually read outside the genre. He does not indulge in sneering, either at SF or litfic. He just sees them as playing different genre games. Which, if I recall correctly, means that he and Joanna Russ could have found subjects on which to agree.…

Science Fiction: New Trends and Old • essay by Alexei Panshin and Cory Panshin

My reading of this essay is that the Panshins basically see SF’s course as run. All that remains to SF is playing with established tropes. The next frontier is “speculative fantasy”!

I could make a snarky comment about extruded fantasy product, but … even when SF was so new that someone could write the first “trapped unaware on a doomed generation ship” story, there was a whole lot of extruded science fiction product.

Of course, the Panshins were pretty much on the mark about fantasy eating SF’s lunch.

The Creation of Imaginary Worlds: The World Builder’s Handbook and Pocket Companion • essay by Poul Anderson

FINALLY! MATH AND GRAPHS! Although, sadly, no equations. Using an imaginary world named Cleopatra, Anderson shows how to give such worlds verisimilitude by drawing on the science of the day. I may moan about this detail or that detail of Anderson’s fiction, but damn! did I love his willingness to sketch out billions of years of planetary history for a backwater world — for a minor novel. There’s no reason fictional planets should be any less diverse than fictional characters.

Cleopatra was used for a shared world project.

Anderson really loved those, for some reason.

[Editor’s note: sharing the slog of worldbuilding.]

[Author’s note: no, I think it was more that Anderson loved worldbuilding and was happy to provide that service to others. And perhaps he liked the back and forth of group projects. Although, as I recall, he was very particular in his choice of collaborators.]

The Creation of Imaginary Beings • essay by Hal Clement

Less math than the Anderson essay but basically a guide to sketching believable aliens rather than believable planets. Clement makes an interesting point: just because you’ve done a lot of homework does not mean you have to present all of it on the page. What the reader needs to know and what the author needs to know are not the same thing.

Hitch Your Dragon to a Star: Romance and Glamour in Science Fiction • essay by Anne McCaffrey

To modern eyes, her ideas about obligate gender roles can seem quaint. McCaffrey also sprinkles her essay with off-handed queer-bashing.

I myself once posted about this small section of her essay2:

“One top-flight writer of sf has been chided for using only one type of heroine: the sort of earnest, if attractive, females who joined the Communist party in the ’30s, the Army in the ’40s, did social work in the ’50s, and started communes in the ’60s. A girl who would ‘die’ for a principle. Great, but girls don’t ‘die for principles. Men do. A girl marries the clunk and converts him to her way of thinking later. In bed.”

But she goes on to explain how she tried to subvert editorial expectations in this matter, to sneak liberated women and even ess ee ex scenes onto the pages of Analog. That single paragraph is misleading absent context.

In some ways, this essay is the most interesting piece in the book, both for what it includes and what absences in the other essays it underlines. For example, remember that oft-quoted Sturgeon comment that in the 1970s “nearly all of the top newer writers, with the exception of James Tiptree, Jr., were women”? You might think a symposium compiled in the early 1970s would reflect that state of affairs. If so, you are terribly wrong. Aside from one or two references to authors like Henderson, women are almost as absent from the text of this book as they are from the list of authors (both as individuals and as a class). Most of the women mentioned in this book are mentioned by this McCaffrey essay. The index confirm this: as far as Bretnor was concerned, the whole of the subject of Women and SF was encompassed by McCaffrey’s essay.

McCaffrey takes a pretty broad view of her remit, so you get a McCaffrey-eye view of the history of women in SF, in general and as it related to her career.

She makes the point that memorable stories are the ones that make some sort of emotional connection to their readers. In the process, she makes it clear she was quite widely read in the SF of the day, and not at all hesitant to mock elder figures whose female characters were … lacking verisimilitude.

McCaffrey is also one of the very few authors in this collection to provide hard data to support the assertion that the number of women in SFWA grew between 1965 and 1970: from 30 to 52. However, as the total membership rose from 275 to 425 over the same period, the proportion of the membership that just happened to identify as female remained more or less the same. I believe the fraction is close to 50% now (correction invited, if necessary), which I think means there are around 900 women in SFWA.

Plausibility in Science Fiction • essay by Gordon R. Dickson

Dickson on how to convince readers to invest in what is after all a fable.

Science Fiction, Teaching and Criticism • essay by Jack Williamson

Williamson, who came to academia later in life, provides an overview of the place of science fiction in college-level discussions. Previously not considered worth studying, SF courses had exploded in the previous decade.

General comments:

Most of the book is interesting primarily as a period piece. If that’s the sort of thing that turns your crank, you may want to check your favourite suppliers of used books. I suspect your best bet may be your local academic library.

1: It might a good idea to reread this symposium; it contains a Brunner essay I’ve been citing here and there over the decades. It would be interesting to see what relation my memory of the essay has to its actual contents. A local academic library has a copy. Stay tuned for possible abject error corrections. Or perhaps smug back-patting.

2: McCaffrey does not mean Heinlein, because she singles him out by name for approbation elsewhere. It may be that she is referring to Larry Niven’s A Gift From Earth, whose revolutionary movement — the Sons of Earth — had, if memory serves, one shrew, one woman there to service the men’s sexual needs, and one (understandably) axe-crazy extremist.