You’ll Get The Message By The Time I’m Through

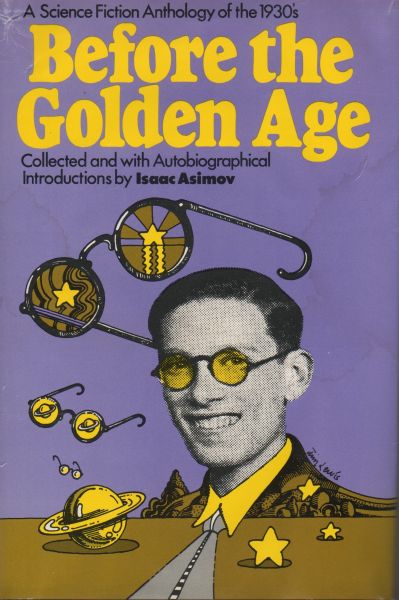

Before the Golden Age

Edited by Isaac Asimov

17 Jul, 2022

Isaac Asimov’s massive 1974 Before the Golden Age is, as its cover subtitle promises, a “Science Fiction Anthology of the 1930s.” In one sense, the subtitle is accurate: the stories predate the supposed golden age of SF, that period between 1938 and 1950, after John W. Campbell, Jr. became editor of Astounding and before Galaxy and The Magazine of Science Fiction and Fantasy offered a broader vision than that offered by Campbell and his idiosyncratic tastes.

In another sense, the subtitle is quite false.

These stories are drawn from Asimov’s personal golden age as a reader, the stories that impressed a young Asimov. Asimov was just eleven when the first story in this volume was published and only eighteen when the final one was published (coincidentally, eighteen was also the age at which a precocious Asimov made his first sale, although the story would not appear until Asimov was a comparatively elderly nineteen).

Given Asimov’s age when he imprinted on these stories and the comparatively rudimentary state of the field at the time, it is not terribly surprising that many of the stories in this 986-page anthology are what professionals call “stinkers.” Kids got no taste.

In my defense, I read this in 1974 because I was interested in the history of the field, there being no hobby I cannot somehow transform into homework. Also because beggars cannot be choosers. Waterloo Public Library had a copy, so I read it. WPL acquired new SF more slowly than I could read books, so I reread it several times. When I happened across an (in retrospect) ominously cheap reprint in a used book store, I snapped it up in an exuberance of nostalgia (not unlike Asimov’s when he edited the volume). Thanks to the Great Rogers Internet Outage of 2022, I have suffered through it again. Now it is your turn.

The volume offers some points of interest. First of all, it’s an indication of Asimov’s prominence at the time that he could convince his publisher to back such a self-indulgent project as a nearly 1000-page assembly of sometimes classic but more often dreadful stories from the ancient past (1931 being as far in the past to 1974 as 1979 is to 2022). Second, Asimov provides each story with commentary, commentary that while providing fascinating context for the tales is not blind to their frequent faults. Thirdly, Asimov is a subject as dear to Asimov’s heart as was science fiction; the volume provides a wealth of autobiographical material about Asimov’s early life. One cannot take all of the material at face value. Asimov is probably pretty good on the events but not necessarily their significance. He seems, for example, to believe that he grew into a suave ladies’ man, as opposed to the sex pest he actually was.

Not all of the stories are dreadful, although many are. Of note (at least of historical note, if not literary): The Man Who Awoke, Sidewise in Time, The Parasite Planet, Old Faithful, and Proxima Centauri.

A sidenote: I finished this big book in one go. I thought I had lost the knack of powering fast through large books. Turns out all I needed was badly written, unchallenging prose.

Before the Golden Age is out of print. Note for people resorting to Abebooks: the 1988 Black Cat / Macdonald & Co. edition leaves out Past, Present and Futureand The Men and the Mirror.

Now about those stories …

“Introduction (Before the Golden Age)” • (1974) • essay by Isaac Asimov

Asimov explains the genesis of this tome.

“Part One: 1920 to 1930 (Before the Golden Age)” • (1974) • essay by Isaac Asimov

Some autobiographical notes on Asimov’s early life, as well as a discussion of science fiction as it existed in the early part of this century.

“Part Two: 1931 (Before the Golden Age)” • (1974) • essay by Isaac Asimov

In addition to brief commentary on each story, Asimov also provides commentary on major developments in his life during the year that he’s covering, as well as the major developments in science fiction.

“The Man Who Evolved” • (1931) • short story by Edmond Hamilton

What wonders will accelerated human evolution offer the world?

This demonstrates the author’s failure to grasp how cosmic radiation affects living organisms, his firm commitment to orthogenesis, and the protagonist’s discovery of dangers of hubris, all in one.

The Jameson Satellite • [Professor Jameson] • (1931) • novelette by Neil R. Jones

Revived by kindly cyborg aliens who discover Jameson’s corpse orbiting a long dead Earth, the professor is forced to decide whether to embrace the new life offered to him or choose personal extinction instead.

Submicroscopic • [Submicroscopic • 1] • (1974) • novelette by Captain S. P. Meek

The protagonist’s shrinking machine delivers him to a submicroscopic world of adventure, true love, and offensive racist stereotypes.

Awlo of Ulm • [Submicroscopic • 2] • (1974) • novella by Captain S. P. Meek

Having embiggened himself to get more firearms, the hero returns to the submicroscopic world for more adventure, further developments in true love, and a different assortment of offensive racist stereotypes.

It would not surprise me if the writer of The Incredible Hulk vol. 2 #140 (someone named Harlan Ellison, perhaps best known for being a supporting character in Scooby-Doo! Mystery Incorporated) had this Meek series in mind when he sent Hulk to a submicroscopic world.

Tetrahedra of Space • (1931) • novelette by P. Schuyler Miller

American adventurers and an assortment of offensively portrayed

South American natives struggle to defend the Earth from Mercurian settlers.

The bit that caught Asimov’s attention was the alienness of the Mercurians, who are not simply weird humans.

The World of the Red Sun • (1931) • novelette by Clifford D. Simak

Americans transported to a distant future thanks to an insufficiently tested time machine are presented with the chance to free the Earth from its cruel overlord. Their reward is bitter indeed.

Note to self: test time machines with very small journeys whose failure will not be catastrophic.

“Part Three: 1932 (Before the Golden Age)” • (1974) • essay by Isaac Asimov

Historical context for the exciting year of 1932.

Tumithak of the Corridors • [Tumithak • 1] • (1932) • novella by Charles R. Tanner

Humanity of the far future cowers in subterranean corridors, believing that the Earth’s surface will forever be the domain of the technologically superior Venusian shelk. It falls to one brave man to prove that this need not be so.

I thought it interesting that the adventure is recounted long after the fact, by historians of the even farther future. They are unclear as to which parts of Tumithak’s adventures are historical fact and which pure myth. They are, however, pretty sure he did not, as legends claim, live to be 250 years old.

The Moon Era • (1932) • novella by Jack Williamson

An insufficiently tested space ship delivers its lone passenger to the Moon of the distant past, where he gets to play a role in the final episode of a ruthless, genocidal war.

To be fair, model spaceships of this design had already vanished into the past and at least one scientist understood why. Our hero just went ahead anyway. ‘

“Part Four: 1933 (Before the Golden Age)” • (1974) • essay by Isaac Asimov

1933 in SF and in Asimov’s life.

The Man Who Awoke • [The Man Who Awoke • 1] • (1933) • novelette by Laurence Manning

A wealthy man uses a cunning method to sleep away the millennia, waking to discover that our era is seen by the future as a time of unforgivable waste whose inhabitants deserved death for their crimes. The implications for his life expectancy once he explains who he is are rather dismal.

As Asimov points out, while the prose is pure pulp, the ecological and economic concerns would have been timely in 1974.

Tumithak in Shawm • [Tumithak • 2] • (1933) • novella by Charles R. Tanner

The further adventures of Tumithak!

This is terrible and also long.

“Part Five: 1934 (Before the Golden Age)” • (1974) • essay by Isaac Asimov

Historical context for 1934.

Colossus • [Colossus (Wandrei) • 1] • (1934) • novelette by Donald Wandrei

Fleeing Earth just as world war breaks out, our hero transcends space and time and ascends to a higher dimension in which our cosmos is merely an atom. He learns many interesting things at the cost of total isolation from humanity.

Born of the Sun • (1934) • novelette by Jack Williamson

A few brave souls struggle to save humanity (or at least white people) from certain planetary doom and the machinations of a devilish Asian cult.

As you may have guessed, this piece is incredibly racist. It must have been so much fun for Asimov to be Jewish in this time and place.

Sidewise in Time • (1934) • novella by Murray Leinster

Ambitious Professor Minott attempts to find an alternate history that offers him the power and respect that should be his. The students he drags along with him are increasingly unenthusiastic about the adventure.

If not the first alternate history story, this is one of the most notable early examples. It is the classic story from which the Sidewise Award takes its name.

Old Faithful • [Old Faithful • 1] • (1934) • novelette by Raymond Z. Gallun

Consigned to death by the Martian autocrat for the crime of uselessness, Number 774 spends its final days focused on the Martian scholar’s singular obsession: the planet Earth and its weirdly unMartian natives.

Notable because the story is mainly told from the perspective of Number 774. I always confuse this story with Eric Frank Russell’s 1950 Dear Devil.

“Part Six: 1935 (Before the Golden Age)” • (1974) • essay by Isaac Asimov

Historical perspective on the year 1935.

The Parasite Planet • [Ham Hammond] • (1935) • novelette by Stanley G. Weinbaum (variant of Parasite Planet)

On a Venus that is life-bearing but only questionably habitable from a human perspective, an adventurer sets out in pursuit of wealth and finds true love instead.

Weinbaum’s tide-locked Venus is not just life-bearing, but excessively life-bearing; it hosts many energetic, voracious lifeforms.

Proxima Centauri • (1935) • novella by Murray Leinster

The Adastra survived more than four light years, seven years, and one mutiny to reach the Sun’s nearest neighbor, Proxima Centauri. Proxima’s dominant civilization welcomes the visitors … as a delectable new snack for the intelligent, carnivorous plants.

This story has one of those space drives that should never be legalized: induced total conversion, which can and at one point does convert an entire planet’s mass into energy. Although this is not technically a generation-ship story, it is one of the tales that introduces a vital element of traditional generation-ship stories: a mid-voyage mutiny.

“The Accursed Galaxy” • (1935) • short story by Edmond Hamilton

All too curious humans discover the dreadful reason that all other galaxies flee the Milky Way.

“Part Seven: 1936 (Before the Golden Age)” • (1974) • essay by Isaac Asimov

More fascinating historical anecdotes, including the very important acquisition of an Underwood Type 5 typewriter by Asimov.

He Who Shrank • (1936) • novella by Henry Hasse

A brilliant scientist works for many years to figure out how to shrink normal-sized entities. He believes he has succeeded and tests his invention on a hapless acquaintance. The unfortunate acquaintance is doomed to spend eternity shrinking into one subatomic realm after another.

This has a twist (one that I won’t spoil) that distinguishes it from the usual run of subatomic realm adventures.

The Human Pets of Mars • (1936) • novella by Leslie Francis Stone

Collected as pets by visiting Martians, a collection of humans must escape their captors and return to Earth, lest they perish at the tentacles of the unintentionally abusive Martians.

Young Asimov had a documented hostility to women SF authors, which may explain why this is the only story by a woman in this enormous anthology. He does acknowledge Stone as a pioneer (while taking aim at the story’s various flaws).

“The Brain Stealers of Mars” • [Penton and Blake] • (1936) • short story by John W. Campbell, Jr.

Terran explorers struggle to determine which of their number are actual humans and which are shape-shifting aliens passing themselves off as humans.

This was reworked into Campbell’s 1938 Who Goes There?, which appeared just a bit too late for Asimov’s self-imposed cut-off date.

“Devolution” • (1936) • short story by Edmond Hamilton

A chance encounter with visiting aliens provides an unfortunate human with a superior grasp of humanity’s rightful place on the evolutionary ladder.

“Big Game” • (1974) • short story by Isaac Asimov

A heretofore lost early Asimov, in which the true cause of the dinosaurs’ demise is revealed.

“Part Eight: 1937 (Before the Golden Age)” • (1974) • essay by Isaac Asimov

Same as before, but for 1937.

“Other Eyes Watching” • [A Study of the Solar System] • (1937) • essay by John W. Campbell, Jr.

A non-fiction piece focusing on Jupiter.

The entire series of essays is online here.

Minus Planet • (1937) • novelette by John D. Clark, Ph.D. [as by John D. Clark]

Humanity is endangered by the approach of a world composed of pure antimatter!

Past, Present and Future • [Past, Present and Future] • (1937) • novelette by Nat Schachner

Not content to be worshipped as a god by the Mayans, a Greek named Kleon contrives to sleep the centuries away. Two thousand years later, a careless American exploring Kleon’s hiding place succumbs to the sleeping gas. Together American and Greek awake to the even more distant future: the Age of the Olgarchs!

Part Nine: 1938 (Before the Golden Age) • (1974) • essay by Isaac Asimov

Asimov makes contact with other fans, in particular a group that would be known as the Futurians, Campbell takes full control of Astounding, and Asimov inches ever closer to becoming a filthy pro.

The Men and the Mirror • [Colbie & Deverel] • (1938) • novelette by Ross Rocklynne

A cop and a crook become trapped in a frictionless, mirrored bowl. Escape depends on ingeniously applied physics!

This is a very early example of hard SF, which is, to quote someone or other, “SF that provides enough technical detail that the reader can be certain that various mechanisms and events couldn’t work the way the author has them working.”