A Fistful of Steel

Swastika Night

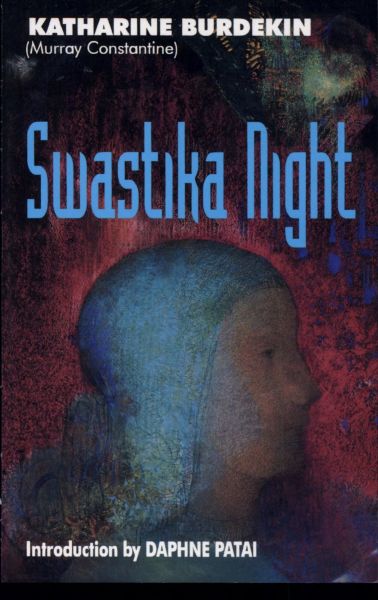

By Katharin Burdekin

10 Jun, 2021

Katharine Burdekin’s 1937 Swastika Night is a novel about a fascist dystopia. It was originally published under the pen name Murray Constantine (Some editions still are).

The Twenty Years War ended with Nazi Germany’s utter victory over the other nations of Europe and Africa. Seven centuries later, the Nazi Empire is rivaled only by the Japanese Empire. The pious Germans who dominate Nazi Europe believe with all their hearts “in pride, in courage, in violence, in brutality, in bloodshed, in ruthlessness, and all other soldierly and heroic virtues.” For most Germans, to do otherwise is literally unthinkable.

Hermann is one such German. His reassuringly inflexible world view will be upended when his old chum Alfred re-enters his life.

Hermann met Alfred when Hermann was serving in conquered England. Of course, the two men are not social equals but Hermann, who reserves any manly affections for other men and not the debased beasts called women, is quite fond of Alfred. When Alfred appears on a pilgrimage of Nazi holy places, Hermann is overjoyed. This is because he misapprehends Alfred’s true purpose.

Incomprehensibly, the English mechanic does not adore the Nazi Empire with all his heart. In fact, he does not care for it at all. Indeed, his attitude could be described as implacably hostile. Hermann should kill the heretic or at least alert the authorities. He finds himself unable to do so.

Hermann is not so hesitant when he encounters a beautiful Nazi boy trying to rape an underage Christian girl. In this era, Christians are a despised underclass. For a proper Hitlerian boy to sully himself in this way, in particular with a pariah below the accepted age for sexual assault, is inacceptable. Therefore, Hermann savagely beats the boy, leaving him mortally injured.

It falls to Knight Friedrich von Hess (knights being one part feudal lord and one part priest; very efficient) to deal with the case. Von Hess is mildly annoyed that the boy was injured, as he is a talented singer, but if the facts were as Hermann claims, then he was within his rights to beat the boy.

Alfred saw the beating but not the events leading up to it. The facts of the case are therefore open to question. However, having met Alfred, von Hess sees that the eccentric Englishman could be useful to the knight, who happens to be just as skeptical about the Nazi faith as Alfred but for better reason. Alfred relies on his reason to deduce that much of what the Nazi regime claims is false. Von Hess owns what may be the last history book in all Europe (which is majority illiterate).

Pious Nazis believe Hitler was a seven-foot-tall blond divine being who exploded from God the Thunderer. Von Hess has an ancient photograph of Hitler that proves he was all too mortal. Furthermore, von Hess’ ancestor carefully documented the process by which modern day Hitlerist religion arose more than a century after the Twenty Years War. Nazi history is an artifact, a farrago of willful lies and deliberate historical erasure designed to create the stratified brutal world in which Hermann, von Hess, Alfred, and millions of others live.

Von Hess is interested in Alfred because von Hess has no living son to whom he can entrust the ancient account. When he dies, the authorities will examine his belongings. They will inevitably discover the forbidden history the von Hess family has preserved for centuries. Upon discovering it, they will destroy it. Von Hess’ hope is that by entrusting the book to the unconventional Alfred, it will be saved for a better future after the Nazi Empire falls.

Of course, that bold plan is predicated on Alfred managing not to provoke some passing Nazis into killing him, an outcome which is very much not guaranteed.

~oOo~

It is a minor plot point in this 1937 novel that the Nazis had already exterminated the Jews. Lacking designated pariahs, they turned their hatred and contempt to the few surviving Christians.

A few years after this book was published, people would be claim to be astounded that the Nazis did exactly what they said they wanted to do. Burdekin wasn’t fooled. This was less due to her taking a very dim view of Nazis than her taking a very dim very of the mindset of which Nazis are merely a prominent example. It does not take much effort to find similar events in the history of the nations from which Germany took its example. Indeed, it takes more effort to overlook those events.

Although this was published under a male byline, critics speculated that the author was a woman. One reason for suspecting this is because although the central characters — Hermann, von Hess, and Alfred — are all men, a considerable fraction of the book is devoted to the status of women in the world seven centuries hence. Under the Nazi regime, women are seen as loathsome animals that must be tolerated because they are necessary to human reproduction. Even Alfred, by the standards of this era a freethinker, finds it nigh impossible to accept that women are people, as capable as men when allowed to be.

This triumph of toxic masculinity is global. The Japanese Empire (1) is just as dreadful. Even the Christian remnant has adopted the misogynist creed. Needless to say, the world that results is comprehensively unpleasant, even for the men who run it. Nobody escapes the worldview that permeates everything. In many cases, they are entirely unaware that things could be otherwise.

There are consequences. The great empires are doomed [2] because women, having learned to hate themselves, are no longer having female babies. Populations are plummeting. Neither militaristic power can afford to go to war with the other, as they lack manpower.

Writing as she was outside the demands of pulp fiction, Burdekin feels no need to comfort the reader with the spectacle of a grand revolution that overthrows Nazism. In fact, the revolution Alfred hopes for cannot be a spectacular one. A change in worldview is a subtle change that isn’t especially plot friendly. The book ends when his movement is yet in its infancy; it’s not clear if it will succeed or not. Look elsewhere for uplifting tales of malice overthrown.

The novel is quite effective in its depiction of what a world according to Nazi beliefs (and those like it) would be if those beliefs were taken to their logical extreme [3]. It’s not at all a comforting book, but it’s highly effective. I thought it a skillfully written nightmare that readers will appreciate and remember. I wonder how it was that Swastika Night fell out of print for generations before being rediscovered in the 1980s.

Swastika Nightis available here (Amazon US), here (Amazon Canada), here (Amazon UK), here (Barnes & Noble), here (Book Depository), and here (Chapters-Indigo).

1: The Japanese Empire is described in comprehensively racist terms, its successes written off as proof of the Japanese talent at copying superior cultures. Everything we see is filtered through the protagonists and one should expect a certain level of bigotry from Nazis and their subjects. In any case, the Japanese Empire is much larger and more populous than the Nazi Empire.

2: Seven hundred years is a pretty good run for enterprises on the scale of the Nazi and Japanese empires.

3: Arguably, no worse than Sparta. But only because Sparta was horrible.