Breathe Deep The Gathering Gloom

X‑Men: Days of Future Past

By Chris Claremont & John Byrne

18 Aug, 2022

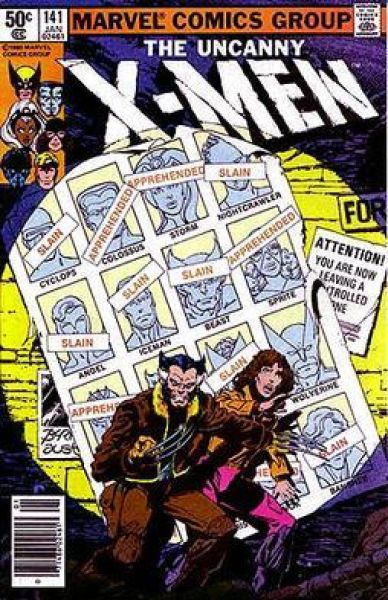

1981’s X‑Men: Days of Future Past was a two-part story that first appeared in the comics X‑Men 141 and X‑Men 142. Chris Claremont was credited as writer, John Byrne as artist; the pair shared plotting credit.

In the unimaginably distant year of 2013, New York’s Park Avenue is a vast slum, as is New York itself. Indeed, New York’s condition reflects the dismal state of America as a whole: an economically declining dictatorship whose population is regimented by the giant robot Sentinels along eugenic lines. Put simply, it’s mutant versus human!

Baseline humans are citizens to the extent any 2013 American can be deemed a citizen. Those who carry unexpressed mutant genes are second-class citizens, subject to sterilization. Mutants with actual super-powers are for the most part executed on detection, although a few, like Katherine Anne “Kitty” Pryde, simply have their powers suppressed and are forced to serve a state that would prefer them dead.

Having killed or confined all the mutants in subjugated USA and occupied Canada, the doctrinaire Sentinels believe it is now time to provide the rest of Earth with the benefits of Sentinel rule. The other nations of Earth differ. Those armed with nuclear weapons are even now readying them should the Sentinel armies begin global conquest. The result can only be total human extinction … unless the surviving mutants can put into action a desperate plan.

Smuggled components allow Katherine and her allies to circumvent their power-dampening collars and escape bondage. Once free, mutant Rachel sends Katherine’s mind back through time to teen-aged Kitty Pryde’s body. It’s up to Katherine-in-Kitty to convince the other members of the X‑Men that she is not mad, and that they must act now to prevent the rise of the Sentinel state.

At that time, Senator Robert Kelly is a presidential candidate. He is loudly, publicly anti-mutant and is therefore targeted by the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants1. By murdering the anti-mutant Senator, the Brotherhood hopes to demonstrate that it is a bad idea to oppose Homo Superior. The assassination had the opposite effect. It inflamed public alarm and hatred for mutants. The result was a sweeping electoral win for anti-Mutantism and eventually, the Sentinel project.

Katherine-in-Kitty knows the time and location of assassination. If the X‑Men act swiftly enough, they can intervene. But will that be enough?

~oOo~

Presumably “Days of Future Past” was inspired by the similarly titled Moody Blues album.

Non-mutants in the Marvel universes had the most remarkable ability to discern on sight whether superhumans were mutants or not. Mutants were generally viewed with deep suspicion, whereas people who gained power through other means were given the benefit of the doubt. Days of Future Past establishes early on that the Sentinels see all superhumans as threats; thus the non-mutant superheroes whose gravestones are shown in one scene.

To be fair: to the easily panicked American electorate, life in a world where garishly costumed superhumans resolve their political differences by leveling neighborhoods must be rather stressful. It may not help that X‑Men/Brotherhood fights are at the low end of the power scale, as cosmic threats are a near annual occurrence.

This is a classic Silver Age Bronze Age Marvel story, which is to say conflict resolution involves shouting (if in-team) or fists-and-energy-bolts (if between teams). As well, confrontations tend to follow strict conventions: the bad guys do well at first, but in the end the X‑Men are a team and teamwork trumps malice2. A comforting moral. This could also be considered plot armor. Yes, they can lose a little at first (suspense!) and less popular X‑Men may die but they must ultimately win. Although not so decisively as to preclude further adventures.

Days of Future Past is also a showcase for John Byrne’s art. While a step up from his Rog-2000 days, this outing shows that Brynes’ repertoire of faces is still pretty limited.

There are parallels between Days of Future Past and 1982’s God Loves, Man Kills, not least of which is that both were mined for X‑Men movies. It’s not surprising that both centre on anti-Mutant sentiment, since the X‑Men are all about anti-Mutant sentiment and how mutants should react to that. Both feature codas that make clear that while the immediate crisis has been resulted, the issues that drove the crisis have not. Clearly Claremont and Byrne knew a good thing when they saw it and were not going to rule out reincorporating elements of the story in future arcs. At the same time, they didn’t want to paint themselves into the same corner Legion of Superheroes painted itself into with the Adult Legion story arc3; by the end of 142, the X‑Men of the 1980s succeed in avoiding Katherine’s 20134, so future X‑Men authors are not constrained to make their stories fit the 198×−2013 timeline featured in this story.

Superhero deaths were not new in 1981, but they were uncommon. Having notoriously durable Wolverine reduced to an adamantine skeleton5 was definitely attention getting. As well, in contrast to the conventions of the day, Claremont elects to focus on the women: in 2013, it’s Katherine who volunteers to go back, and a mutant named Rachel who sends her, while weather controller Storm is the most effective when it comes to damaging Sentinels. Earlier, it’s Mystique and Destiny who provoke the crisis by targeting the Senator and Storm who leads the X‑Men.

This story was quite successful, both in sales and as inspiration for later writers. Many later writers. This specific 2013 wasn’t the future of Marvel-616 but events that echo it occur over and over. Additionally, it was (as previously mentioned) chosen as the source for two of the X‑Men movies.

The X‑Men: Days of Future Past storyline has been collected and is available (along with other material) here (Amazon US), here (Amazon Canada), here (Amazon UK), here (Barnes & Noble), here (Book Depository), and here (Chapters-Indigo).

1: This is the second organization to call itself the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants. The name is misleading: the founder Mystique and precognitive Destiny are women (Mystique is a shapeshifter so fixed gender does not really apply, but she defaults to a female form.). Mystique appropriated the name from mutant supremacist Magneto’s original Brotherhood of Evil Mutants, which alsohad a woman on the roster. Magneto was presumably a sexist, while Mystique was constrained by the brand she was stealing.

Mystique’s Brotherhood had at one time a third woman, power-thief Rogue. I believe she became a member after the Days of Future Past story.

2: The Brotherhood in this story consists of Mystique and her close friend (and as the Comics Code enforcement was relaxed, lover) Destiny, plus the rather bland Avalanche and two monumental jerks, Pyro and the Blob.

3: Do I explain this? Or do I review the arc? Decisions, decisions.

4: The 2013 mutants are not sure if changing the past changes the future or just causes a new future to branch off. The whole adventure may be an exercise in futility from their perspective.

5: Not to mention poor Colossus, even closer to being invulnerable, who is killed off-stage.