Footnotes of Doom

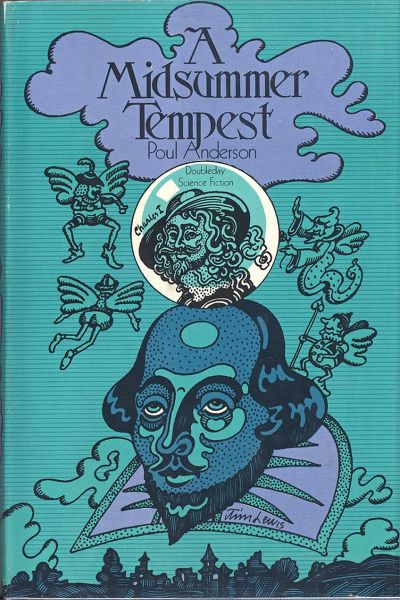

A Midsummer Tempest

By Poul Anderson

15 Jan, 2023

Poul Anderson’s 1974 A Midsummer Tempest is an alternate-history fantasy novel.

Lights up on a familiar scene. The Royalists are trounced by the Roundheads at the Battle of Marston Moor. Royalist commander Prince Rupert flees the debacle but is captured by Shelgrave’s forces. While capture does set-up a meet-cute between Rupert and his captor’s niece Jennifer Alayne, it seems the end of Rupert’s career is at hand.

Despite similarities, there is a crucial difference between this Battle of Marston Moor and the one we know. In this world, William Shakespeare is not the great playwright. He is the Great Historian, whose works record events that actually happened.

Also: this is a world more technologically advanced than that of our historical English Civil War. Not only is England wrestling with disagreements of essential theology, its society is also being upended by an incipient industrial revolution.

The Fair Folk as are real as trees. For them, the industrial revolution isn’t simply the engine of social transformation. It is an existential threat that threatens to erase faerie folk from the world. All is not yet lost, provided a human can be found to accomplish a task beyond faeries.

Awkward lovebirds Rupert and Jennifer offer Oberon and Titania the necessary opportunity. Rupert is just the sort of adventurer who might be able to find Prospero’s lost grimoires. With grimoires in hand, Charles I and an old regime with a place for faeries might be saved. Freeing Rupert proves easy enough. The rest is up to the prince.

Displeased that his guest took leave without permission, Shelgrave begins a dogged pursuit. Here faerie magic betrays the faeries; the very magic rings that Oberon and Titania have used to help Rupert and Jennifer can also be used to track either one of the couple. Rupert can flee but as long as true love persists, Shelgrave will always be able to find him.

~oOo~

Interesting that one of the founders of the Society of Creative Anachronism (in which rulers are tournament winners and rule by consent) would pen a novel in which the good guys are the ones trying to preserve the rule of a would-be absolute monarch. One does note that this world differs from ours not only in the matter of Shakespeare and actual magic, but also in that this world Charles I is said to be able to learn from experience. I will accept Shakespeare the Great Historian, magic, and Oberon ruling faerie with Titania, but a Stuart king who learns from experience seems a bridge too far.

I fear Prince Rupert’s dog Boye fairs no better at this Battle of Marston Moor than he did in the historical one. The battle is also not a great place to be Prince Rupert’s horse. Readers interested in the historical battle could do worse than to hunt down a copy of Strategy & Tactics Magazine 101, which contains a compact but complete wargame simulating that battle.

A question with which most readers are likely wrestling at this point is “Why, when Amazon and other sources list A Midsummer Tempest as the second Holger Danske novel, this review does not? Is this the dreadful specter of semi-pelagianism?” It comes down to a simple disagreement over the significance of an encounter in which I take the correct side while everyone who disagrees is wrong. Lots of room for compromise here!

Partway through the novel, Rupert takes refuge in the Old Phoenix, a tavern that exists between and connects different universe. There he meets Holger Danske, protagonist of Anderson’s 1961 Three Hearts and Three Lions, as well as Valeria Matuchek, a supporting character from Anderson’s 1971 fix-up fantasy novel Operation Chaos. The main purpose of the interlude, the only connection of which I am aware between the otherwise unconnected Three Hearts and Three Lions, Operation Chaos, and A Midsummer Tempest is to ensure that Valeria can discover that Rupert’s Shakespeare is the Great Historian and thus explain the conceit to the readers. It’s a rather clumsy contrivance — John M. Ford would have handled the issue more adroitly — and I am not rewarding it by lumping this novel in with either Three Hearts and Three Lions or Operation Chaos.

Otherwise, this book may be as close to whimsey as was possible for the famously morose Danish American Anderson, particularly at this, the most morose stage of what seems to have been a long-running experiment to see how productive a deeply pessimistic, arguably chronically depressed man could be at this point in Anderson’s career. This novel appeared at about the same time as Anderson’s “The Pugilist” (Anderson completists will understand the significance; the rest of you can take comfort in ignorance) and the somehow even grimmer A Knight of Ghosts and Shadows. A Midsummer Tempest is considerably more upbeat than either.

Anderson took particular delight in worldbuilding, as may be seen in the effort he put into backgrounds of backwater planets he had no intention of revisiting. He also wrote a plethora of essays on the subject. Working out the details of a world that conformed to an anachronistic Shakespeare is just the sort of activity that would appeal to him. It is an interesting world and Anderson has fun with it. Of particular note is the vocabulary, which is rather Shakespearean. Too bad that Anderson never returned to this setting.

The book was a reader favourite. A Midsummer Tempest won the 1975 Mythopoeic Fantasy Award1, was a finalist for the 1975 World Fantasy Award (Best Novel)2 and the Nebula3, and came in nineteenth for the Locus Best SF Novel4.

A Midsummer Tempest is available here (Amazon US), here (Amazon Canada), here (Amazon UK), here (Barnes & Noble), and here (Chapters-Indigo). I did not find A Midsummer Tempest at Book Depository; their current edition appears to be an ebook.

1: Beating How Are the Mighty Fallen by Thomas Burnett Swan, Merlin’s Ring by H. Warner Munn, Prince of Annwn by Evangeline Walton, The Forgotten Beasts of Eld by Patricia A. McKillip, and Watership Downby Richard Adams.

2: Losing to The Forgotten Beasts of Eld by Patricia A. McKillip while coming in ahead of Merlin’s Ring by H. Warner Munn.

3: Losing to The Forever War by Joe Haldeman, finishing behind The Mote in God’s Eye by Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle, Dhalgren by Samuel R. Delany, The Female Man by Joanna Russ, and A Funeral for the Eyes of Fire by Michael Bishop, while finishing ahead of Autumn Angels by Arthur Byron Cover, Doorways in the Sand by Roger Zelazny, Guernica Nightby Barry N. Malzberg, Invisible Cities (translation of Le città invisibili) by Italo Calvino, Missing Man by Katherine MacLean, Ragtime by E. L. Doctorow, The Birthgrave by Tanith Lee, The Computer Connection by Alfred Bester, The Embedding by Ian Watson, The Exile Waiting by Vonda N. McIntyre, The Heritage of Hastur by Marion Zimmer Bradley, and The Stochastic Man by Robert Silverberg.

Checking my notes, this is the very year whose lengthy list of finalists managed to smother my attempt to plagiarise Jo Walton’s Hugo Project by changing the focus to the Nebulas. It is an impressively diverse list! But also, very long. So very long.

4: So many novels get nominated for the Locus that I usually settle for links. Having provided all the Nebula finalists, I may as well do the same for the Locus. I am regretting my life choices at this point in time.

The winner was The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia by Ursula K. Le Guin. The finalists that placed higher than Anderson’s novel were The Mote in God’s Eye by Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle, Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said by Philip K. Dick, The Godwhale by T. J. Bass, The Unsleeping Eye (variant of The Continuous Katherine Mortenhoe) by D. G. Compton, Inverted World by Christopher Priest, Fire Time by Poul Anderson5, The Forever War by Joe Haldeman, The Dream Millennium by James White, The Twilight of Briareus by Richard Cowper, The Company of Glory by Edgar Pangborn, The Gray Prince by Jack Vance, The Forgotten Beasts of Eld by Patricia A. McKillip, How Are the Mighty Fallen by Thomas Burnett Swann, Total Eclipse by John Brunner, The Destruction of the Temple by Barry N. Malzberg, Stargate by Stephen Robinett, and Star Rider by Doris Piserchia. A Midsummer Tempest came in ahead of Prince of Annwn by Evangeline Walton, Walk to the End of the World by Suzy McKee Charnas, Icerigger by Alan Dean Foster, and A Knight of Ghosts and Shadows by Poul Anderson6.

5: Poul Anderson was very prolific.

6: Seriously, very, very prolific. Even more prolific than that. 1974 saw publication of the novels Fire Time, Star Prince Charlie (with Gordon R. Dickson), and the serialization of A Knight of Ghosts and Shadows, as well as the shorter My Own, My Native Land, The Voortrekkers, Passing the Love of Women, “The Visitor,” and A Fair Exchange, not to mention such LOCs, essays, introductions, afterwords, and commentary as Afterword (The Voortrekkers), How To (The Bulletin of the Science Fiction Writers of America, Summer 1974), Letter (Vector 67/68), Memoirs of a de Camp Fan, Special Notice from Poul Anderson, The 1974 Nebula Award Nominees (1974), The Creation of Imaginary Worlds: The World Builder’s Handbook and Pocket Companion, Entertainment, Instruction or Both?, Dictionary Compiled While Listening to a SFWA Conference, Letter to The SFWA Forum #32, January 1974, Letter: On the Harpplaying Hero, Letter (Algol, May 1974), The Worth of Words, A World Named Cleopatra, Reply to a Lady, The Wizard of Nehwon, Editorial (Thrilling Science Fiction, August 1974), Forum: A Cyclical Theory of Science Fiction, and Reading Heinlein Subjectively … The Reaction. I doubt that is anything like a complete list and this was when Anderson was a geriatric forty-eight years old, likely older than the Appalachian Mountains7.

The lesson here is that we could all be writing more than we are.

7: From the perspective of a thirteen-year-old farm kid.