Give Your Smile to Me

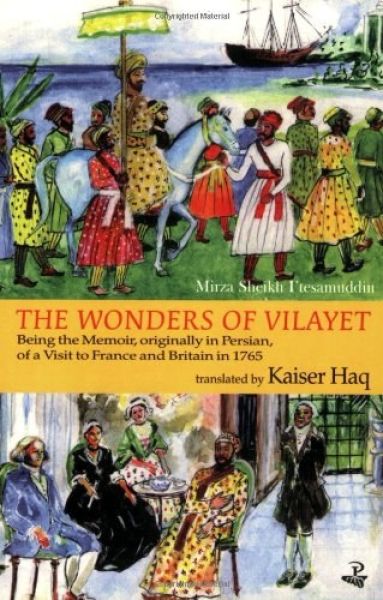

The Wonders of Vilayet: Being the Memoir, Originally in Persian, of a Visit to France and Britain in 1765

By Mirza Sheikh I'tisām al-Dīn (Translated by Kaiser Haq)

5 Jan, 2022

The Mirza Sheikh I’tisām al-Dīn’s The Wonders of Vilayet: Being the Memoir, Originally in Persian, of a Visit to France and Britain in 1765 is a travel memoir, recounting the Mirza’s tour of France and Britain in 1765. The English translation is by Kaiser Haq.

The Bengal-born functionary had been a munshi, a secretary, for the nawabs of Bengal and the British East India Company. In 1765 he set out on a diplomatic mission to Britain on behalf of the Mughal Empire. The Mirza would learn only too late that his mission had been sabotaged by Robert Clive1, making the entire endeavour a wasted effort. But the diplomatic failure nevertheless resulted in a fascinating memoir.

The account is short, just 132 pages. Nevertheless, into those pages the Mirza crams sixteen chapters. He begins with a terrifying sea voyage from India to England. The vessel on which the Mirza traveled is more seaworthy than it appears and it is not lost with hands. However, had the weather been even more hostile or the navigation less skilled, the ship certainly could have been lost, a fact of which the Mirza was quite aware.

The vessel puts in at France, a nation whose poverty astonishes the Mirza. French citizens’ endless bragging fails to impress. It’s probably just as well the French did not dominate India, because the Mirza does not think much of them.

No sooner does the Mirza arrive in England but it is discovered that he has violated the stringent British customs laws. This is due to ignorance on his part and is, after some back and forth, forgiven.

Once disembarked in England, however, things go altogether better. The Mirza astonishes and delights the English2 with his unfamiliar clothing and customs. The English impress the Mirza with their work ethic, scientific arts, and multitude of astonishingly beautiful women3. Their relentlessly brutal legal system seems to have horrified him4. Being painfully aware that the balance of power in India was tipping from the Mughals to the English, he struggles to figure out what strengths the English had that the Mughals lacked.

Of course, there is the matter of religion. The Mirza is Muslim while the English are Christians of various sorts. Between them lies a great gulf of history and misunderstanding. Curiously, whenever the Mirza debates the English on matters of religion, he always comes off the winner. Or so he says. However, he may be the only literate Muslim in England and is thus considered a curiosity and not a threat. Conversations remain amiable even as he cheerfully consigns all Christendom to hell for their flawed doctrine5.

Had matters played out differently, he might well have remained in England the rest of his life. The Mirza was at the time the only person in England who was able to read and translate Persian documents, a skill valuable enough to scholars that they explored the possibility of providing him with one (or even more! in accordance with his customs!) English wives. However, he missed India and returned home once it was clear that his diplomatic mission was pointless.

~oOo~

About the title: a vilayet is an Ottoman administrative district. I do not know how it became associated with Europe in general, and England in particular (sometimes London in particular). However, we live in a world in which Europeans refer to Native Americans and Indians (from South Asia) by the same word despite their homelands being unrelated regions half a planet from each other … so I am inclined to give the Mirza a pass on this matter. I do wonder why he consistently refers to Europeans as “hat-wearing.”

The Mirza is aware of and curious about both European history (at least in broad strokes). Sometimes he seems confused about various matters accepted as fact in Europe (the rotation of the moon is a notable example). This could be because translation failed or it could be that he doesn’t know what he doesn’t know6. However, he does his best to relate what he sees as accurately as he can. Most of his observations about European society ring quite true.

The short memoir is told in an engaging, endearing style. Perhaps unsurprisingly for a career diplomat, the Mirza seems to have been a charming fellow who if not always impressed by his fellow humans, was invariably judicious about how he expressed himself while making his views perfectly clear. His account is an entertaining view of England from the outside.

The Wonders of Vilayet is available here (Amazon US), here (Amazon Canada), here (Amazon UK), here (Barnes & Noble), and here (Book Depository). Yet again, I failed to find a book by a particular POC at Chapters-Indigo.

1: Clive was determined to protect the East India Company’s control of India, which require kneecapping direct diplomatic contact between the Mughals and the English.

2: I almost said British — but everything he experiences in Britain is filtered through English sensibility, thus the Scots come off as robust, energetic knuckleheads.

3: He could never marry in England because the women of sufficiently lofty class would never wed an Indian. While race might not be an insurmountable impediment to marriage with lower-class women, he could not marry beneath him.

That said, his knowledge of the nature and location of English brothels appears to have been encyclopedic.

4: Mind you, he finds Hindu customs absurd. It’s probably for the best that he’s an Indian Muslim and a servant of the Mughal Empire.

5: He is antisemitic, in spite of (or possibly because) having seen few or no actual Jews prior to visiting London, which has a comparative abundance.

6: His grasp of European history is likely a lot better than any given Englishman’s grasp of Indian history. He dwells on one point on the problem of determining historical fact, his example being the widely varying versions of Alexander the Great.