Glory Days

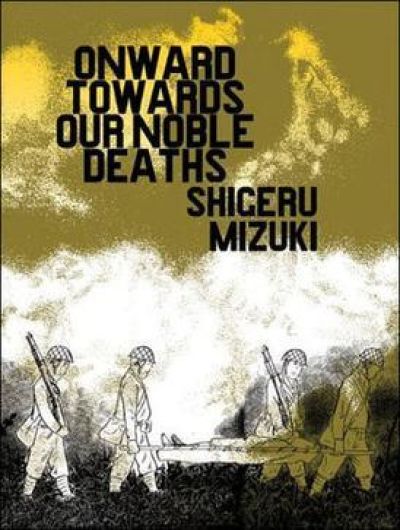

Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths

By Shigeru Mizuki

10 Jul, 2024

Shigeru Mizuki’s 1973 Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths, is a stand-alone historical tragedy manga. Titled Sōin Gyokusai Seyo! in the original Japanese, the 2011 English translation1 is by Jocelyne Allen.

Imperial Japan sent Private Murayama and others off to New Britain island in Papua New Guinea, there to join the Baien Battalion in tropical isolation.

New Britain proves something less than a paradise.

The issue is not the natives, whom the Japanese soldiers never see. Nor are the Americans an immediate threat, although their occasional raids are worrisome. The environment, while challenging, is nothing humans have not managed for thousands of years. The pressing danger that faces the men is their own army.

The high command in Japan has no regard for the well-being of its soldiers. Therefore there are no real efforts to deal with the supply chain issues inherent in occupying New Britain. Therefore the men are poorly fed. Therefore the men are sickly. Therefore soldiers die in droves from malnutrition and disease.

Making matters far worse than they need to be is the army culture. Soldiers are kept in line with endless abuse from above. Punishment is erratic, often given without any justification. The NCOs are convinced that brutality ensures obedience and they embrace their duty enthusiastically.

Why is unthinking obedience so important? Because officers like Major Tadokoro are completely deranged. If the soldiers were in the habit of thinking about orders, they would never obey the Major’s directives.

The Americans begin their campaign into Japanese-occupied territory. If the goal is to use the meagre resources available to slow the Americans as much as possible, the prudent choice would be for the Baien Battalion to withdraw to defensible positions, then conduct guerilla warfare. This would be hard and ignoble.

Major Tadokoro has a much better idea: order a suicide attack. That way all of his men will die immediately without the bother of an extended campaign, and they will die having accomplished nothing. It will be a glorious death.

Murayama and a handful of others do the unthinkable. They survive. The army has a legion waiting in Rabaul for their chance to die pointlessly. How can the army expect the soldiers in Rabaul to follow orders if people like Murayama insist on living?

The army’s emissary of death is dispatched to address the crisis.

~oOo~

Shigeru Mizuki’s manga is semi-autobiographical2. He was drafted and sent off to New Britain; he returned home short an arm. His fellow soldiers did not return home at all. The experience appears to have soured the artist on being brutalized by thugs on behalf of madmen in pursuit of impossible goals.

It would be easier to mock the Japanese high command if their philosophy were not so reminiscent of what I will unhelpfully call Donner Party conservatism, the belief that misery is both ennobling and necessary. (See also this essay.)

The Imperial Japanese were brutal occupiers. That does not play a role in this story, as the locals appear to be avoiding the Japanese. It is interesting that Mizuki is said to be been invited by the indigenous Tolai to remain after the war; the occupiers cannot have been quite as terrible as they were elsewhere (or perhaps the artist was exceptional). However the absence of the indigenous people in the story means the author is free to underline that the Japanese were almost as brutal to the Japanese as they were to everyone else.

Mizuki uses two very distinct art styles. Backgrounds and other elements are nearly photorealistic. His cast of Japanese characters is drawn in a simple, and cartoonish manner. Despite the simple style, the art is often evocative, particularly in the facial expressions of men realizing just how doomed they are.

The style does blunt somewhat the various incidents of graphic violence. Given how frequently people are dismembered, this is probably for the best3. Still, don’t worry that this is an endless sequence of heads flying off or people being reduced to fragments. Some people simply bleed to death, expire of fever, or are drowned and partially eaten by the local crocodiles.

Best not to read the manga expecting last minute saves, sudden attacks of reasonableness, or a swift end to the Pacific War that will save the soldiers. It is a tragedy after all.

Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths is available here (Amazon US), here (Amazon Canada), here (Amazon UK), here (Barnes & Noble), here (Chapters-Indigo), and here (Words Worth Books). I did not find Onward at Apple Books.

1: Onward was the first of Mizuki’s manga to be translated. I am saving his Showa for August.

2: As the afterword explains, he took some liberties with the fate of one character to streamline the narrative.

3: There is a 2007 television adaptation of this manga. I wonder how the director handled the violence?