House of Cards

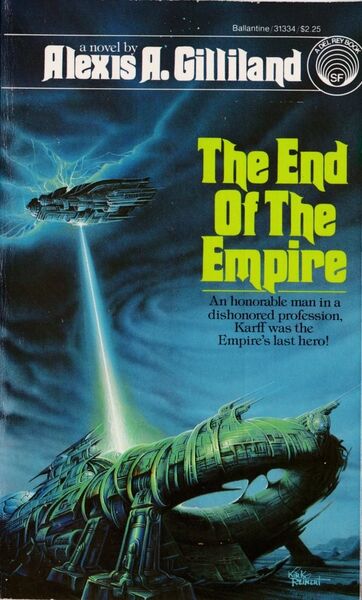

The End of the Empire

By Alexis A. Gilliland

17 Apr, 2025

Today’s review: The End of the Empire by Alexis Gilliland, published in 1983. I last reviewed this short novel a quarter century ago. I really hope I don’t recapitulate point for point my comments in the original review. I trust this is a fresh look.

The Holy Human Empire was neither holy, nor entirely human, nor an empire. The Holy Human Empire was as mortal as any institution. The government that once ruled many systems had been reduced to portions of a single planet. Soon, the empire would not even have that much1.

Faced with certain defeat on Portales, the imperial fleet flees. Amongst the lucky few to escape rebel wrath, intelligence officer Colonel Saloman Karff.

Karff presents a problem for General Bloyer. Karff correctly suspects that Bloyer was dealing with the rebels. Karff has said as much. Bloyer therefore needs to find some way to rid himself of Karff before Karff can find evidence to condemn Bloyer.

The only world within reach of the fleet where they can reasonably hope to reprovision is Malusia, ninety-four days beyond the edge of the former empire. Once there, the fleet will have to decide whether to stay or to continue its flight.

Initial impressions are of a very odd society ripe for imperial conquest. Centuries ago Malusia and its system were settled by fanatical anarchists from Portales. The founders were determined to prevent the rise of a powerful government. Therefore, they embraced institutions too weak to properly govern, but strong enough to prevent formal government from appearing.

Among the consequences: Malusia is in the process of being terraformed. It is not used for agricultural purposes, but as a dumping ground for surplus population. Food is grown in space habitats. All cargo makes its way down via a single orbital elevator. From time to time, the elevator breaks down. Famine results.

The wealthy families in space believe all options to mitigate the recurring crises fall into two categories: too expensive or politically hazardous. Therefore, their policy is to do nothing and accept that from time to time some large percentage of the population down on the planet will starve.

The political situation combined with the fact that the system is technologically backward presents the imperials with an opportunity. A cunning intelligent officer could exploit existing social fracture lines to help under-raise a local government or more accurately, facilitate imperial conquest. Karff being sufficiently cunning, Karff is handed the job.

However, should the rebel fleet pursue the imperials, the imperial fleet would have to flee the system on short notice. There would be no time to retrieve Karff and his staff. An excellent development for General Bloyer.

Bad news for Karff and for Malusia, both left to the mercies of the rebel fleet.

~oOo~

Readers should be aware that despite the brevity of the novel, Gilliland is quite keen on pausing every once in a while, for worldbuilding exposition.

Unsurprisingly for a book dedicated to Dominic Flandry and Jaime Retief2, the Holy Human Empire is a marvel of corruption and ineptitude. Karff is competent (to the extent that his role allows it), honest (to the extent that his role allows it), and (to his enormous misfortune) loyal officer who serves an empire despite being aware of its flaws. Unlike either Flandry or Retief, Karff is unlucky enough to experience the empire’s abrupt implosion. The lesson here, for all cynically patriotic intelligence officers, is to pick one’s period carefully.

A bit surprising given all the above: Empire is a comedy, if a rather grim one.

For some reason, I was certain that this novel had been considered for the Prometheus Award or at least its Hall of Fame. This was very much not the case. On reflection, I don’t know why I thought this, as Empire is not at all a love letter to either anarchists or libertarians. Or government in general.

There are three governing systems on display here:

- The Holy Human Empire, which is as previously stated wildly corrupt and incompetent.

- The rebels, who are reminiscent of the socialist factions on the losing side of the Spanish Civil War or perhaps the communist factions on the winning side of the Russian Revolution. We learn little about them, none of it complimentary.

- The Great Holders of Malusia, who are relentlessly doctrinaire, inflexible, and perfectly willing to allow famine after famine on Malusia to preserve their way of life. If it comes to it, they will nuke Malusia to prevent the peons from creating functional institutions3.

The rebels owe their existence to a technological innovation; both the Holy Human Empire and the Great Holders are technologically conservative, and for the same reason. Innovation would and does undermine their power.

The reader gets a good look at the HHE and all its quirks. The reader gets an even better look at the glories of a libertarian regime, and all the benefits those living under it do not experience. Therefore, no surprise if Gilliland never got (or will get) a Prometheus nod.

Curiously, Analog’s Tom Easton seems to have come away with quite a different impression than I did.

Look back at the Rosinante books. Gilliland is a libertarian writer, for his point is consistently freedom from too-controlling governments, personal rather than institutional integrity and independence. It’s a stance that allows good yarns, as the opposite one can rarely do, and it has much to recommend it.

Lack of institutional integrity dooms the empire. Malusia’s problem is that because it is libertarian, it’s stuck, unable to create the government that further development requires. I think in fact Gilliland is not exactly a libertarian author, at least not in the usual sense, or Malusia’s libertarian establishment would not be routinely starving its people, whenever it’s not considering nuking them.

I’d say read and decide for yourself, but The End of the Empire is very sincerely out of print.

1: USA delenda est.

2: Curiously, the dedication misspells Dominic as “Domenic”.

The book seems plagued with minor errors: the copyright credits the cover art to Ralph McQuarrie. The artist’s signature, which is clearly visible on the cover, is Kirk Reinert’s. Did McQuarrie create a cover that was not used?

3: To the Great Holders’ credit, they’ve done a bang-up job of indoctrinating their people to the point that very few Malusians can imagine alternate ways of doing things.