No Angels Above

High-Rise

By J. G. Ballard

17 Oct, 2023

J. G. Ballard’s 1975 High-Rise is a thrilling tale of modern lifestyles.

Recently divorced doctor and lecturer Robert Laing is persuaded by his sister to sell his Chelsea home and move into a very modern tower block. Forty floors tall, the edifice offers the inhabitants of its thousand apartments every amenity a late-20th century British person could want. If humans could build a modern-day urban Eden, it would look like Laing’s new home.

This modern-day Eden goes as well as the mythological Eden.

[Pet lovers may want to stop reading at this point.]

Life in the high rise seems ideal. It offers a self-contained community. Stores and entertainment are only elevator rides away, as are willing partners for joyless assignations. At first glance, there seems to be no reason why anyone would want to leave, were it not for work.

At first, the snow-globe community appears to function well. But it does not take too much time for the inherent divisions between the inhabitants to manifest. Indeed, if one asked architect Anthony Royal, stratification was not merely inevitable. It was intentional, a reflection of how society is supposed to be structured. However, there are emergent properties the doomed architect did not foresee.

The tower block isn’t cheap. Therefore, anyone who can afford to live there has to be reasonably affluent. However, there are an abundance of occupations that provide sufficient income. The inhabitants may share affluence. Class differences still divide them. These are reflected by placement in the building. Royal’s fellow upper-class folk live at the top of the building. Merely successful lower-class folk live at the bottom. Useful professionals like Laing live somewhere between.

At first, the inhabitants avoid those who are too dissimilar. Then, they begin actively discouraging forays into their designated territories by those too dissimilar. It does not take long for this apartness to become violent. Having divided along class lines, the next logical step is social atomization. Society collapses, replaced by a Hobbesian war of all against all. It’s a glorious triumph … for the predators.

~oOo~

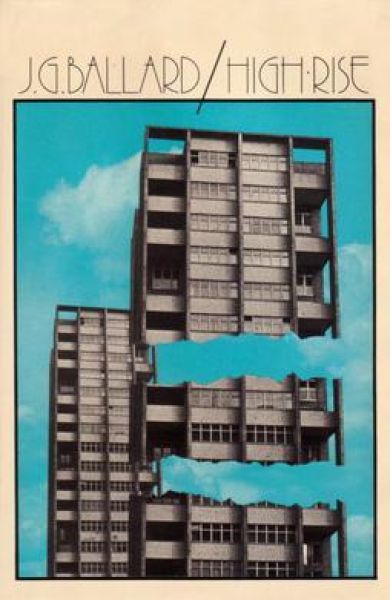

Usually I use the cover art for the edition I own but the edition I own is the 1977 Pather with a memorable Foss unsuitable for social media. Original cover it is!

The novel begins with Laing eating a barbequed dog, so it’s not surprising that events develop not necessarily to the benefit of the building’s inhabitants. Just knowing the author’s name is enough to hint that the high rise won’t be a latter-day Eden. This new society turns out to be no society at all. People are free to indulge their worst impulses, which of course they do.

Before communication breaks down between the inhabitants, it breaks down between the high rise and the outside world. Curiously, nobody outside the building takes notice, not even when people fall from the upper floors onto cars and sidewalks below. Panicky 999 calls might have attracted the notice of the emergency services. Silence does not.

This isn’t a story about the dreadful consequences of concentrating the lower orders in vertical slums. This tower block caters to the well-to-do. Ballard here isn’t critiquing the deplorable tendencies of the underclasses. Ballard is pessimistic about humanity in general. In the correct environment, everyone is only a short cascade of unfortunate decisions away from self-inflicted catastrophe.

One can compare and contrast this with another work of this era about a self-contained community of the affluent, which is to say Niven and Pournelle’s rather dire Oath of Fealty. One vital difference between the high rise and the Todos Santos arcology of Oath is that the American arcology is united by shared hatred and fear of those outside. Also, in a glorious recapitulation of small-town society, Todos Santos is a panopticon state, distinguishable from a prison only because the inhabitants choose to be there. The people of the high rise are free to do as they please.

Thatcher was some years away from reigning in Number Ten when Ballard played with the consequences of “there’s no such thing as society,” yet here we see the implications of Thatcher’s thesis laid out.

The plot, such as it is, is linear and lean. The characters are sufficient to need but not complex. Recognizing this, Ballard does not overstay his welcome, limiting his novel to a slender 200ish pages. The result is not a pleasant read, but it’s certainly memorable.

High-Rise is available here (Amazon US), here (Amazon Canada), here (Amazon UK), here (Apple Books), here (Barnes & Noble), and here (Chapters-Indigo).

Oddly, Chapters-Indigo’s search engine produced no results for High-Rise by J. G. Ballard. I had to search on the author, then look through all of the books by him listed on the site.