So Hard To Find

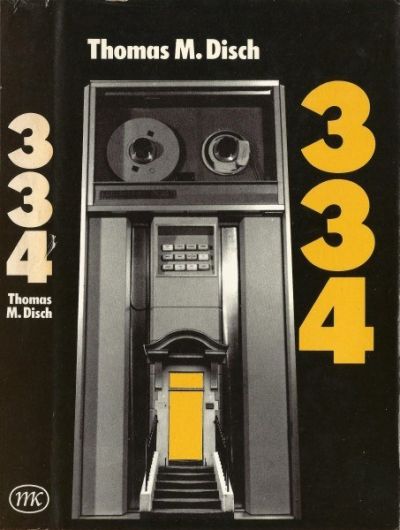

334

By Thomas M. Disch

14 May, 2024

Thomas M. Disch’s 1972 334: A Novel is an examination of a small American community: the residents of 334 East 11th Street.

In 1972, this was a futuristic work set in a New York City of the mid-2020s. What unparalleled wonders, novel freedoms, and bewildering prosperity awaited Americans in that far-off era, so distant from 1972 that conventional dating can barely encompass it?

In fact, someone from 1972 would find 2025 crowded but surprisingly familiar. While medicine has progressed, as have drugs, America’s technological progress has been less than wonderous. Also, familiar prejudices prevail and society is as stratified as ever. Perhaps some people enjoy the prosperity that Disco-Era Americans hoped might be in their future—but not those domiciled at 334 East 11th Street.

Umbrella welfare agency MODICUM provides the inhabitants of 334 with the basic necessities. Luxury is absent, but the residents have just barely enough. It is hoped that this will prevent revolutionary fevers from spreading. 334 is primarily a storage facility for those currently surplus. Some (perhaps a few youths) might find their way out of 334 and into rewarding careers (or if they opt for military employment, a short but memorable one). Many will not.

This work is primarily composed of vignettes, such as:

- A young man unhappy to discover he’s just under the eugenic minimum for permissible reproduction.

- A necrophiliac brothel that discovers too late that their latest illicit acquisition will be missed.

- A drug-sozzled mother pondering educational options, options contextualized by visions of a crumbling Roman Empire.

- A troubled couple wrestling with the complications of a very modern marriage.

- Bored teens who decide to fight boredom with bouts of homicide.

There are a number of vignettes about one family in particular.

While this may not be the world of the future the characters might have wanted, it’s the one they got.

~oOo~

Is 334 actually a novel? Opinions may differ. I myself hold the common-sense position that this is in no sense a novel, even if the author slapped “a novel” on the cover. If the author were to have titled it 334: An Elephant, that would not have made 334 an elephant. Not even a very small elephant. However, I accept that people are free to be wrong on this point.

There are authors who write surprisingly non-futuristic futuristic novels1 through lack of imagination. However, the technological pessimism in this novel is, I suspect, a deliberate choice. I suspect that it was inspired by the sentiments eloquently expressed in a Marcus Aurelius quotation that appears in the text:

“Consider the past: such great changes of political supremacies. One may foresee as well the things which will be. For they will certainly take the same form. Accordingly, to have contemplated human life for forty years is the same as to have contemplated it for ten thousand years. For what more will you see than you have seen already?”

Thus we get a future with superficial differences, some minor changes in social mores2, but one to which a Nixon-era American could adjust over the span of a coffee break. In fact, such a person might find actual modern arrangements more alien, as 334 features a Great Society that has been preserved and extended, rather than being essentially undermined and discarded, as it was in the real world3.

Oddly, 334 seems to have been overlooked by the conventional reviewers of the era, Locus being the main exception. If Galaxy, If, Analog, or F&SF took note of it, the ISFSB does not document this. Given that F&SF reviewer Algis Budrys reacted hostilely to earlier Disch work, being ignored might have been the better option. Still, the book managed to make it into David Pringle’s Science Fiction: The 100 Best Novels4 despite not being a novel. 334 managed a Nebula nomination in 1975 despite having been published in 1972. Clearly, it had its fans.

As long as one sets aside any expectation that the characters will be anything but deeply flawed, something readers should have done as soon as they saw “Thomas M. Disch” on the cover, and as long as the reader doesn’t expect a conventional structure, 334 rewards reading. Disch paints a vivid portrait of an America in the unimaginably distant year of 2025.

334 is available here (Amazon US), here (Amazon Canada), here (Amazon UK), here (Barnes & Noble), here (Chapters-Indigo), and here (Words Worth Books).

1: One non-futuristic futuristic element that might appear speculative to modern readers: eugenics. MODICUM’s application of eugenics to its unfortunate charges isn’t some novel application of the nanny state but rather the extension of practices common when Disch was writing.

2: For example, “Republican” and “Democrat” have somewhat different meanings in 2025 than they did in 1972.

3: Readers should also discard expectations based on the fact 334 is often billed as a dystopia. It’s no worse than today in many respects and better in others. Since we live in the best of all possible worlds, and 334 is slightly better, it follows that 334 must be a utopian novel.

4: David Pringle’s Science Fiction: The 100 Best Novels is a non-fiction text discussing the one hundred science fiction novels that Pringle believes are the best. I am pretty sure I have Science Fiction: The 100 Best Novels upstairs. No idea how I’d review it.