Some Forgotten Dream

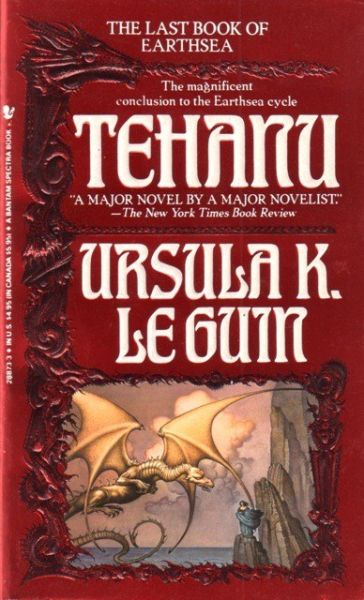

Tehanu (Earthsea, volume 4)

By Ursula K. Le Guin

27 Jun, 2024

1990’s Tehanu: The Last Book of Earthsea is the fourth of at least six volumes in Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea secondary-universe fantasy series.

As a young woman, Tenar was a priestess to the Nameless Ones. She chose to flee. Tenar was offered a place in cosmopolitan1 Havnor. She chose backwater island Gont instead. Adopted by the old mage Ogion, Tenar was offered a chance to learn magic. She chose to marry a farmer named Flint instead2.

Tenar did not choose to become a widow living alone. Time chose that for her.

As a child, Therru either fell or (more likely) was thrown into a fire. Tenar was able to save Therru’s life, but could do nothing to save the girl’s eye, or the function of one hand, nor could she wish away Therru’s scars. While the simple people of Gont tended to react in fear and hatred towards the disfigured girl, Tenar adopted Therru and raised her as Ogion had raised Tenar.

Not all that long after an aged and ill Ogion dies uttering unnecessarily oblique advice about Therru, Tenar adopts another foundling. This one is an adult. Due to the events of the previous book, former Archmage Ged has lost all of his magic. Ged has no idea how to proceed or even if he should. It falls to Tenar to care for Ged while he wrestles with the horrible prospect of being a regular person.

More challenges await. Therru’s supposed uncle Handy covets Therru, claiming love as his motivation. Nothing about Handy or Therru’s history before adoption supports Handy’s claim of sincerity.

Most ominous: the mage Aspen dislikes Tenar and despises Therru. His first attempt to curse Tenar fails. Mages like Aspen are nothing if not resolute. Failure only inspires further effort.

What can a widow, a disfigured girl, and a mage without magic do against Aspen’s malice?

~oOo~

Having read this back-to-back with The Farthest Shore, it seems to me that Le Guin’s vocabulary is simpler in Tehanu than in Shore. Was this a choice or something forced on her by time?

Bad news first: I still have no idea what it was about this book that triggered heated arguments thirty years ago. Given the state of Usenet archives, I suppose I will have to come to terms with never knowing. Other authors appear to have liked it, judging by the fact the novel won a Nebula.

Speaking of coming to terms with disappointments, Ged is an example of what happens when a formerly able-bodied person discovers they cannot simply walk off a new setback. Presumably going out in a blaze of glory would have suited Ged better than suddenly finding himself stripped of an ability on which he always relied. To say he does not adjust gracefully to this development is an understatement.

Among the many ways in which this novel differs from the previous ones: Tehanu provides a closer look at what life is like for people who are not mages like Ged or nobility like The Farthest Shores’ Arran. It’s not great, particularly for women. Sure, things are even worse for Tenar’s Kargish people, but peasants have few protections from lords, wives have none from their male relatives, and everyone should be at least a bit cautious around mages, a number of whom deserve to have “the ha ha ha mad” appended to their official names3.

As I suspected it might, Tehanu addresses the matter of women in Earthsea. In a twist that will no doubt astonish readers, it turns out that the confidence with which characters dismissed women’s magic is not entirely founded in fact. One might go so far as to say it’s flat out wrong. Women’s magic (or at least the schools that they can practice without mages getting huffy4) may not be as flashy as sorcery, but it seems to be considerably more useful to the peasant on the street. This attitude towards women’s magic appears to be rooted in the general views about women, which can be exploitative, dismissive, or hostile. Or all three.

This new light on Earthsea culture is compatible with what’s shown in the earlier books. The difference is that in this book, it is the focus.

Tehanu: The Last Book of Earthsea is available here (Amazon US), here (Amazon Canada), here (Amazon UK), here (Apple Books), here (Barnes & Noble), here (Chapters-Indigo), and here (Words Worth Books).

I am not entirely certain that it really is in print in the UK, as opposed to some bookseller having inadvertently stuck a few copies on an obscure back shelf.

1: At least as cosmopolitan as one gets on Earthsea.

2: Le Guin’s depiction of love and marriage is about as joyless as Andre Norton’s, who is not an author I would otherwise associate with Le Guin. Tenar certainly wanted marry Flint (or at least someone) but reasons for marrying mentioned in the book involve practical issues like financial security and who takes care of the goats, not luxuries like love.

At the risk of annoying a lot of Le Guin fans, there are parallels with my experience of Le Guin’s fiction. In many cases, I can rattle off a list of reasons why people might consider reading Le Guin novels but actually enjoying them on anything aside from an austere intellectual level usually is not among them. Well, not every book has to have pew pew pew or swoony moments.

3: Although this is a world where true names have power, it’s a rare person who does not have a variety of names, applied depending on context.

4: Ogion at least seems to have thought women could be sorcerers, given the proper training.