Some Get By

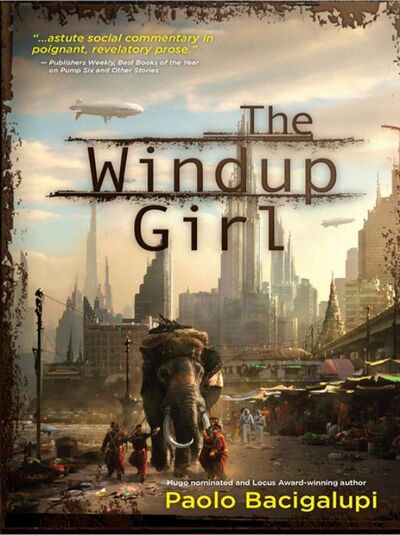

The Windup Girl

By Paolo Bacigalupi

18 Mar, 2025

Paolo Bacigalupi’s 2009 The Windup Girl is an award-winning cli-fi novel.

The end of cheap oil combined with rampant climate change have brought nation-states and international trade to their knees. This has not prevented giant agribusiness from extending their power across the planet. As engineered blights obliterate public domain plants, the hungry masses are forced to embrace copyrighted, genetically-engineered crops.

Plucky little Thailand is one of the few holdouts. It’s Anderson Lake’s task to crush Thai intransigence.

Thailand has to some extent escaped the general disaster by sealing its borders and imposing strict import regulations. As a result, most of its people are still alive and it can feed itself without being dependent on the agribusinesses’ sterile seed stocks. These regulations are enforced by the so-called “white shirts” of the Environment Ministry. The ministry has preferred to err on the side of diligence rather than human convenience, human rights, or even the exact wording of the law. Enough time has passed since the big plant plagues that the common people and those malevolent plutocrats who would take advantage of them to have forgotten why fanatical devotion to the ecological rules and national closure are important. This presents Lake with an opportunity.

Lake’s ostensible job is manager of AgriGen’s spring factory. Stupendously powerful springs, wound by genetically-engineered megadonts, are the power supply of tomorrow. Too bad that most of the springs that Lake’s factory produces are defective. Nevertheless, the factory provides a reason for Lake to be in Thailand.

A marketplace fruit stand suggests to Lake that a precious secret seed bank is hidden somewhere in Thailand. The Finnish seedbank was destroyed during a bid to commandeer it. Lake will have to be careful as he moves to take control of the Thai seed bank.

Step one is finding the seed bank. Here, Thailand’s unsavory sexual practices play into Lake’s hand. Abandoned by her Japanese owner to save on shipping costs, genetically-engineered Emiko — the Windup Girl of the title — is a sex slave owned by the depraved Raleigh. Emiko is able to provide Lake with valuable information, in return for which Lake reveals to Emiko that some so-called “New People” have fled their invariably cruel masters for a secret refuge.

Meanwhile, Jaidee, the Tiger of Bangkok, one of the more visible white shirts, is ever vigilant against threats to Thailand. His unbending determination makes him something of an embarrassment to the government. More importantly, his fanaticism means he is a serious impediment to the more ethically flexible Thai functionaries. Left to his own devices, Jaidee might have confounded Lake. As it is, he spends much of the book contending with his colleagues.

Lake buys goodwill from Thai functionary Somdet Chaopraya by revealing to Somdet that Raleigh’s brothel has a windup girl. The depraved Somdet provides Lake with useful concessions, then focuses his attentions on the unfortunate Emiko.

Subjected to increasingly horrific rapes on Somdet’s orders, Emiko realizes that no matter what Raleigh promises, Raleigh will never free her. Emiko expresses her displeasure by barehandedly massacring everyone in Raleigh’s club.

Among the dead, Somdet. The consequences ripple through the government and reshape Thailand.

~oOo~

The Windup Girl is replete with unfortunate stereotypes of Asian people. Like all too many American SF novels. Readers may wish to discuss this issue in comments.

Other readers might be appalled at the novel’s use of grotesque, lavishly described sexual violence as a motivator. Well, it was all the fashion back in the early 21st century. My old records show that about one in five of the books I received from the SFBC featured motivational rape, except during one memorable six-week period in which I received forty-seven books in a row with that plot detail. Indeed, some people found the concept that works could feature women who were not raped utterly incomprehensible.

My report for the SFBC included the line “I would like it understood that only my legendary professionalism prevents me from filling this report with an obscenity-filled rant about the utter stupidity of his worldbuilding.” As it happens, I am under no such restriction here.

Remember Peak Oil? It was a big thing fifteen years ago. Actually, there’s nothing unreasonable about the idea that at some point a finite resource would run out. In fact, concerns about Peak Oil turn up at least as long ago as Harrison Brown’s 1954 The Challenge of Man’s Future1, perhaps even earlier. The SF authors who embraced Peak Oil seem to have shared a blind spot about the human tendency to find replacements for goods no longer readily available.

Case in point: while the danger of coal burning is acknowledged and dealt with (even the evil giant evil corporations concede that adding more CO2 to the atmosphere is unacceptable), this is a world where solar power does not appear to have become cheaper, nuclear energy does not seem to exist, and hydroelectric power (which currently supplies more than 60% of Canada’s electricity) appears unknown. In fact, “solar,” “nuclear,” and “hydroelectric” do not appear in the novel’s text.

What the Windup Girls’ world does have are a bunch of stupid giant springs, which are wound by stupid genetically-engineered megadonts. The energy density of those springs is implausibly, hilariously high; one could power a single-stage-to-orbit rocket with them, if one could somehow harness their energy to reaction mass.

Why the hell would anyone with a spring whose storage capacity challenges the limits of matter think that the best way to wind them is with an animal? Only a very small part of the energy generated by the food eaten is accessible to animals and only a small part of that is exploitable by the animals’ owners. I am sure there must be less efficient ways to charge power storage devices, but I cannot think of one.

While I am discussing dubious worldbuilding choices: the author tells us that Peak Oil has largely undermined international trade. The only reason I can see that anyone would quibble with this plot point is if even steep shipping price increases would have a marginal effect on the cost of shipped goods, which as it turns out is the case2, or if somehow it turned out world trade predated the era of cheap oil, which as it happens it did.

I will grant the mass-deaths and general collapse of civilization will have done trade no favours, but I dwell on shipping costs because they are directly relevant to another part of the plot.

The shipping cost detail figures directly into the plot because the expense of shipping Emiko is what led her owner to abandon her in Thailand. Now, not only did Emiko have to be created in the first place, her education involved one-on-one tutoring. How expensive does shipping have to be that it costs more per kilogram than the cost of producing a new, adult, artisanally-educated slave like Emiko? And how are even the rich traveling if it is that expensive?

Why does this all matter? Because to hold this book up as the darling of cli-fi novels, a book whose worldbuilding is complete and utter tripe, raises the same questions that 2312 did: if the author is completely out to lunch about basic details, why trust their conclusions about the big issues? In fact, isn’t nonsense like this a weapon for climate-change denialists?

Of course, The Windup Girl won awards. So many awards: the Hugo, the Nebula, the Campbell Memorial, the Compton Crook, the Best First Novel Locus, the Kurd Lasswitz Prize, the Seiun, the Premio Ignotus and the Imaginaire. No doubt there were others.

Still, it is a rare book that doesn’t have even one virtue. The Windup Girl’s virtue is this: it single-handedly kept Nightshade Books afloat much longer than would otherwise have been possible. Alas, I no longer have the Bookscan data, but I recall that there was a period in which sales of The Windup Girl were a significant (and I want to say dominating) fraction of Night Shade’s sales in general. Which would be pretty impressive if I weren’t so bitter about the novel’s success.

The Windup Girl is available here (Night Shade Books), here (Barnes & Noble), here (Bookshop US), here (Bookshop UK), here (Chapters-Indigo), and here (Words Worth Books).

1: Brown calculated that the US’s entire stock of fossil fuels, of which oil was but a small part, was good for somewhere between 75 to 250 years. Interestingly, Brown does discuss CO2-driven climate change… as a positive development likely too challenging for humans to engineer. I have some very good news for Brown.

2: A forty-foot container can hold about 20,000 blue jeans, so if the shipping cost is $1000.00, then the shipping cost per blue jean is about a nickel per pair of pants. Even if costs go up by a factor of 100, it’s still only $5 per pair of pants.

In this setting, fantastically cheap shipping seems to have fallen by the wayside, while airships for some reason enjoy a golden age. This is because SF authors love airships and prefer not to think of them as fragile kites that require more crew per kilogram to operate than do airplanes.