Sugar And Spice, And All That’s Nice

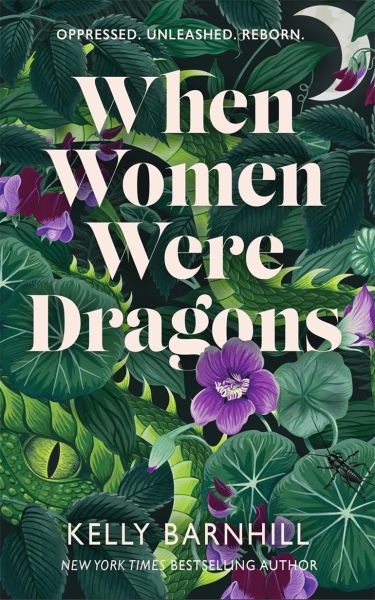

When Women Were Dragons

By Kelly Barnhill

16 Jun, 2022

Kelly Barnhill’s 2022 When Women Were Dragons is a modern fantasy set in the 1950s.

On April 25, 1955, 642,987 American women spontaneously became dragons. The new dragons abandoned their homes for destinations that better suited them. Mass dragoning could not be ignored … but it did not take Cold War America very long to collectively agree that dragoning (mass or otherwise, causes, and whether or not dragoning was a one-off or an ongoing phenomenon) were all subjects unfit for polite conversation. Those reluctant to follow this convention were targeted as un-American and blacklisted.

Alex (not the Alexandra adults around her insist on calling her) Green was too young to dragon, but her life would be transformed by the event.

Prior to April 25, Alex’s life was a fairly conventional one for a young American girl. Her father was a banker, her mother, whose mathematical genius had been suppressed to better fit the role of homemaker, a housewife. After all, of what possible use were intellectual and professional achievements to the women of 1950s America?

The only discordant note in this relentlessly conventional household was the influence of Alex’s aunt Marla, who was a talented auto mechanic. She was pressured into a marriage but it did not turn out well; her husband was a hapless loser whose sole positive contribution to the household was fathering Marla’s daughter Beatrice. Marla vanished on April 25th (as did her husband for related but quite different reasons). Beatrice was left behind. Alex’s family took in the abandoned kid. Now Alex had a new younger sister. Since dragooning was not to be mentioned. her parents firmly insisted that Beatrice had always been part of the family. As far as the Greens were concerned, Marla had never existed.

Alex is being raised to conform. Her intellectual talents, which are arguably as great as her mother’s, are not encouraged. She will just become a housewife after all. Alex’s infatuation with a fellow schoolgirl is also ruthlessly discouraged.

Cancer is a word as unspeakable in the 1950s as dragoning. Alex is aware her mother is unwell but has no idea what’s wrong. Refusing to acknowledge cancer will not cure it. Having lost her aunt to dragoning, a by-now teenaged Alex and young Beatrice lose their mother to cancer.

Whereupon their father suddenly reveals that he is in fact far worse than he seemed to be. Alex and Beatrice’s mother is immediately replaced by their father’s notably pregnant former secretary. Alex and Beatrice are relocated to an apartment of their own. Contact with their father is limited to financial support and occasional phone calls.

Alex navigates high school while playing mother to a younger sister to whom she is steadfastly devoted. She is painfully aware that her father’s support will end as soon as she graduates. She also knows that Beatrice’s mom Marla dragoned and fears that Beatrice may dragon as well. Her devotion may end in heartbreak.

~oOo~

Obligatory “I don’t see how a world in which this one impossible phenomenon occurred throughout history could have produced a world that looked anything like ours.”

You may ask “how often can a young girl patiently correct people using the wrong form of her name without it having any effect on what the adults call her?” The answer to that is “very.” No, even more very than that.

Audiences may find it very difficult to imagine an America where roughly a million people could vanish overnight, where the collective response is to shrug their shoulders and try to pretend nothing happened. Consider this the one impossible thing that enables the plot (like psychic powers or FTL). Perhaps it would be easier to understand if we learn that dragoning is perceived as a feminine process, therefore as unspeakable as pregnancy or menstruation.

This is roughly where prior to, oh, March 2020 I would insert a diatribe about how if angry women were prone to transforming into living weapons of mass destruction one would expect society to take note and take steps to mitigate their anger1, perhaps by offering them more equal roles or at least get them pointed in the direction of rival nations. Apparently dealing with crises by competently addressing their root causes is not what people actually do.

Alex’s father is a heartless, self-centered misogynist, enabled in general by a society that supports his views — but also in specific by his wife. Alex’s mother isn’t just a passive victim of misogyny. She wholeheartedly cooperates in suppressing Alex and Marla. Because the book is very much told from Alex’s point of view, her mother’s motivation is somewhat a matter of speculation. It is not a lack of alternative models: Marla provided one and Alex’s mother was extremely determined to get Marla married off.

That said, Alex’s immediate family is clearly an extreme even at this time. Despite their efforts to stamp out any evidence of other ways of doing things, secondary characters make it clear that while non-conformity has a price, it is an option. These characters provide Alex with the assistance she needs to resist her deplorable parents. So, this story is not all awfulness, all the time, as much as it might have appeared to be such to Alex. It does in fact get better, at least for Alex.

“But aside from that, Mrs. Lincoln, how did you like the play?”

This is a fine example of a genre that was very popular about fifty years ago, the angry feminist novel: see much of Joanna Russ’ work for Sfnal cousins and this classic for mainstream fiction:

It’s an astonishing thing that a book that takes such a dim view of the 1950s should happen to appear just as so many people hail the 1950s as a lost paradise (when their focus isn’t on restoring the 1850s). It’s almost as though authors react to their context, that the same sort of injustices that angered authors half a century will still anger them now.

The plot drags a bit towards the end but on the whole this was a competently executed period fantasy. I am quite impressed by the skill with which the author established Mr. Green as the sort of parent whose obituary is the cause of celebration.

When Women Were Dragons is available here (Amazon US), here (Amazon Canada), here (Amazon UK), here (Barnes & Noble), here (Book Depository), and here (Chapters-Indigo).

1: One might guess that in this timeline, as in the real 1950s, doctors prescribed tranquilizers to housewives unhappy with their lives. Perhaps this might not have kept those housewives from dragoning, but at least their new dragon selves would have been very calm while they set fire to their homes and consumed astonished husbands.

This is not hyperbole: Some dragons definitely eat people, on top of which whole buildings get leveled with considerable loss of life, since the one detail common to all dragonings is that the women are always incandescently furious when they change. Interestingly, a few dragons belatedly try to reenter society later on; presumably the cops leave them alone because one of the things established during the Mass Dragoning is that dragons are essentially invulnerable.