The Darkness Inside You

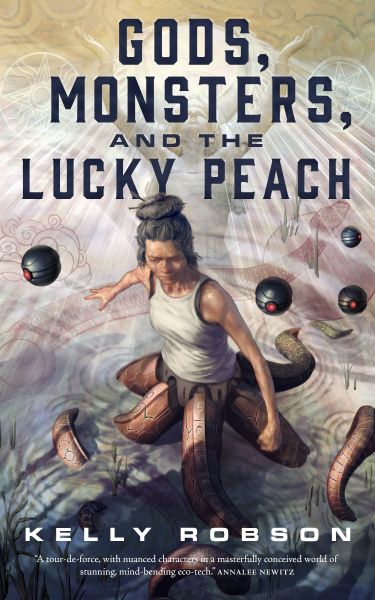

Gods, Monsters, and the Lucky Peach

By Kelly Robson

30 Jan, 2018

Kelly Robson’s 2018 Gods, Monsters, and the Lucky Peach is a time-travel story.

Large-scale ecological remediation used to be a booming field. Then TERN developed time travel and remediation faltered. Bankers were convinced that access to the past would allow immediate remediation of past insults to the environment. Funds for the slow, laborious process of rebuilding the Earth’s ravaged surface have dried up. Like too many rivers.

Minh, one of the ecological remediators whose projects have been sidelined, must face the inevitable: survival means joining the enemy.

The ambitious project to rehabilitate the Euphrates and Tigris River Basins spans both a vast area and long spans of time. It requires forays into 2024 BCE to assess the state of ancient Mesopotamian ecosystems. Minh has no love for time travel, but money is money. Her team is small, but she hopes to convince investors that the right size is an asset.

Winning the bid is only the first step. Next comes the mission into the past. Or rather into a past. Each trip creates a new side branch of history, budding off known history. When the travellers leave, the branch is lost forever, presumably vanishing in a puff of logic. At least that’s the guess; that past is certainly no longer accessible. The travellers are free to act as they see fit, comforted by the knowledge that nothing they do can alter the past.

If the expedition has to kill to survive, those deaths do not count. On the next visit, the corpse is again a living person. This is not the case for the members of Minh’s team. If some Mesopotamian warrior were to put a spear into Minh or any of her team, they would be dead and they would stay that way. This asymmetry counsels the researchers to firmly and quickly deter any local attacks. Even possible attacks. The researchers are hair-trigger murder hobos. Not to worry, say the bosses; it’s not as if the past-timers will stay dead forever1.

And yet, there’s a terrible, irresistible urge to treat exochronic human resources like they were, well, people. No good can possibly come of that.

~oOo~

My take on time travel: if people cannot use their time machines with at least as much ingenuity as Bill and Ted demonstrated in Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure, they have no business having a time machine in the first place. I am happy to report at least one person in this story passes this test.

In this setting, as in so many real world settings, what could be done is far greater than what is actually done. What actually gets done is limited by funding, and thus, politics, In some eras, that means intriguing clerics. In others, catching the attention of a monarch. In this near future, it means convincing bankers, who (in this fictional world) seem to be even more focused on short-term gains than they are in real life (and that is saying something).

On the plus side, aside from some mass extinctions, some plagues, a certain level of catastrophic climate change, and what seems to be the almost complete elimination of humans from the surface of the Earth, the system has worked out pretty well for all concerned. It’s nice to read an upbeat story for once.

Something this book conveys nicely: no matter how shiny the storied future or how whiz-bang its technology, to the people actually living there it is just the mundane present. The bright and shiny post-scarcity future is like the end of the rainbow, always receding from our grasp. Minh and her pals have astounding technology at their command but much of their lives are spend struggling with conflicts a modern person would find very familiar: where is the funding coming from? What are we willing to sacrifice to gain security? How can we avoid feeling empathy for people in cases where there is no business case for empathy?

Robson presents a cast atypical of SF; an old woman, an eager graduate student, and an older colleague, a cast better suited to an academic setting than a bold foray into the past. The closest to a stock SF character the story provides is Fabian, who is just the sort of guy any story needs whenever a young girl must be pushed out an airlock. Curiously, the author seems to take a rather unsympathetic view of Fabian. It’s almost as though the author thinks readers can more readily identify with humane, ambitious researchers quixotically focused on building a better world than on a proper heroic sociopath. I wonder if Robson’s other fiction has a similar bias? No doubt I will find out.

Gods, Monsters, and the Lucky Peach is available here (Amazon) and here (Chapters-Indigo).

1: Which suggests that there is no point to any measures to limit the spread of modern diseases. Still … more suffering, if temporary. Presumably,