The Days of the Old Schoolyard

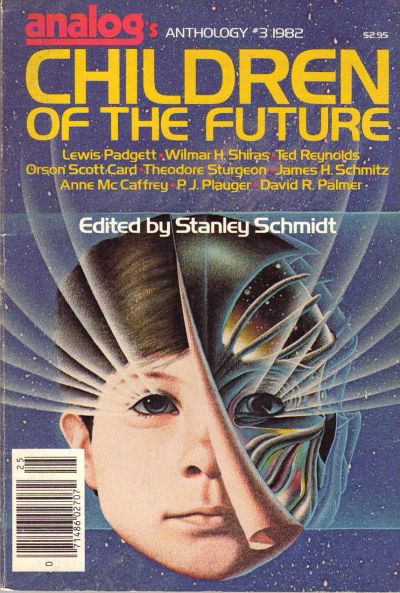

Analog’s Children of the Future (Analog Anthologies, volume 3)

Edited by Stanley Schmidt

1 Jul, 2021

1982’s Analog’s Children of the Future is the third installment in the Analog Anthologies, all of which were edited by Stanley Schmidt. As one might guess from the title, all of the stories are drawn from the pages of Analog(some from the days when it was called Astounding). All of the stories involve children.

Two details immediately caught my eye, neither of which particularly pertains to stories as such. The first thing is that the volume in my hand is not a proper mass-market paperback, nor a trade, nor a hardcover. It is digest sized. Essentially, it’s what a mass-market paperback would look like if it were printed using magazine format. It appears to have stood up to the ravages of time fairly well, but the book is an artifact that makes me wonder why they did it this way1, although perhaps a better question might be why MMPB use a slightly different height to width ratio. Either way, this volume will stand out on my book shelves.

The other thing I noticed was an absence. Like all virtuous people, I check the copyright date on the stories before reading unfamiliar collections and anthologies. No offense to the hordes of moral degenerates who do not! Obviously, the law permits you to make this grievous error. In any case, what this reveals is that while the anthology draws on the previous forty-odd years of Analog, it does not draw from each decade evenly. In particular, the 1940s are over-represented, while the 1950s are entirely absent2.

1940s: 4

1950s: 0

1960s: 2

1970s: 2

1980s: 2

One might guess that the Golden Age of SF effect was at work, but in this case, Schmidt was born in 1944 and his personal golden age should have been in the mid-1950s. Ah, well. It’s a small sample size, so there will be clumping.

This collection can be viewed through several lenses: gender balance, familiarity, status as a classic of the olden times.

Gender balance: there are two stories by women alone and one collaboration involving two people, one of whom was a woman. Otherwise this is an anthology of stories by men, which is not surprising given Analog’s track record.

Familiarity: some of these stories James read long before encountering this collection (eight, to be exact). There were two stories that he hadn’t read (or perhaps had read and instantly forgotten).

Classics: the same eight stories that James remember are the ones that might have been considered classics in their time. The two he never encountered or encountered and forgot: not classics3).

Because I’ve read most of the contents of the anthology, it fell a bit flat for me. Younger or more inexperienced readers, particularly those with a tolerance of the quaint ethos of yesteryear’s Astounding/Analog, might enjoy this. It’s out of print, of course, but copies are easy enough to find.

Introduction (Analog’s Children of the Future) • essay by Stanley Schmidt

An unremarkable intro that briefs the reader on the anthology’s remit.

Mimsy Were the Borogoves • (1943) • novelette by Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore [as by Lewis Padgett]

It’s the distant future and a bored scientist studying time travel sends his son’s toys into the past. One box of toys lands in the 1940s, where the box of educational toys has a dramatic effect on the children who encounter it.

One could, I think, easily put together a collection of 1940s stories about the effects of objects thrown into the past. I wonder if there was any reason for the popularity of the trope beyond Campbell being willing to buy such stories?

Mewhu’s Jet • (1946) • novelette by Theodore Sturgeon

When an alien crash-lands near a holiday cottage, the cottage’s human inhabitants befriend the alien. The language barrier and the alien’s advanced technology prove to have caused serious misapprehensions about the nature of the ET.

The Witches of Karres • [Karres] • (1949) • novelette by James H. Schmitz

A hapless star trader rescues three young girls from slavery and is rewarded by being dragged quite unwillingly from his dreams of a boring conventional life into a life of super-powered adventure.

I was so hoping this story would be short enough that the subplot about the nine-year old girl who sets her cap for the middle-aged hero would be left out … but no such luck.

Mikal’s Songbird • [Songmaster • 1] • (1978) • novelette by Orson Scott Card

A beautiful boy with a wonderous singing voice is drawn into deadly court politics.

This isn’t just about turning children into assassins, nor about thinly veiled homoeroticism. It’s also about the dire need for a Strong Man, someone to competently take charge. This of course justifies extreme measures.

Just about everything I dislike about Orson Scott Card’s fiction is on display here, save for his views on the proper roles of women (because there are no women to speak of in the story). I am a little surprised that Schmidt didn’t go with Card’s 1977 novella Ender’s Game, but less surprised that Card recapitulated many of Game’s gambits in this story, since Game was one of the main things that established his career.

In Hiding • [Children of the Atom] • (1948) • novelette by Wilmar H. Shiras

A psychiatrist tasked with attending to an odd young man discovers (much to his surprise) that the young man is odd not because he is maladjusted, but because he is the next step in human evolution.

This was included in the later fix-up novel, Children of the Atom, which probably helped inspire the X‑Men comic franchise. Quite unlike most works along these lines, the novel-length expansion ultimately comes to the conclusion that segregation of the gifted is the wrong answer.

Weyr Search • [Dragonriders of Pern short fiction] • (1967) • novella by Anne McCaffrey

On an alien world that just so happens to resemble a slew of other secondary universe fantasy settings, a young woman plots to regain the birthright stolen from her. She fails to do so but gains something far more precious.

“Meeting of Minds” • (1980) • short story by Ted Reynolds

A child’s past life regression may be key to understanding why aliens obliterated an entire community of colonists.

If it were not for the (1980) in the original, I would never have guessed this was published as late as it was. I’d have guessed 1940s.

“Novice” • [Telzey Amberdon] • (1962) • novelette by James H. Schmitz

As far as Telzey’s mean aunt Halet is concerned, Telzey’s pet crest cat Tick-Tock is simply something Halet can use to torment her niece. In fact, not only is Tick-Tock the means by which Telzey will begin to realize her psionic potential, the crest cat is the harbinger of a diplomatic crisis that could sweep humans from the face of the crest cat homeworld.

If you’ve qualms about off-handedly rewriting minds for one’s personal convenience, this is not the story for you. At least there are no age-inappropriate romantic subplots.

Odd that this collection has two Schmitz entries.

“Child of All Ages” • [Melissa] • (1975) • short story by P. J. Plauger

Melissa appears to be a child. She is in fact over two thousand years old. The means by which she gains her immortality has a serious drawback, one that means she must always return to hiding amongst the mortals.

Emergence • [Emergence] • (1981) • novella by David R. Palmer

Candidia Maria Smith-Foster believes that she survived World War Three through pluck and the lucky coincidence her father happened to have a lavishly appointed nuclear shelter concealed beneath their home. To her surprise, she discovers that her survival is thanks to her being Homo Superior, the next step in human evolution. Whether or not there are sufficient Homo Superiors left after World War Three to form a viable population is left for the inevitable sequels.

This too would not have been out of place in 1940s Analog.

1: Ben Bova also edited three Analog anthologies but those were proper trade format (by Baronet) and mass-market paperback (by Pyramid and Ace). The binding on the Baronet trades is appalling.

2: Not surprising at all: works acquired by John W. Campbell, Jr. dominate. Well, when this anthology was assembled, Campbell had helmed Analog longer than Bova and Schmidt had between the two of them.

3: Mewhu’s Jet and A Meeting of Minds being the odd ones out. I loath Songbird but I understand why it’s included. If you believe that my judgment as to classic status is skewed by familiarity, tell me why I’m wrong in comments.