The Passing Years

The Best of Astounding

Edited by Anthony R. Lewis

30 Apr, 2023

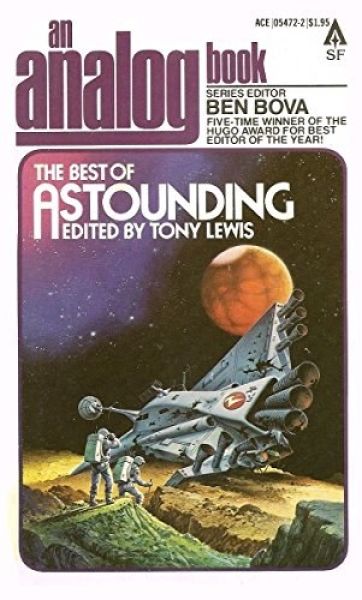

Anthony R. Lewis’ 1979 The Best of Astounding1 is a science fiction anthology. Lewis appears as Tony Lewis. The Best of Astounding was published as part of Ace Book’s Analog Book series.

There were only eleven books in this series:

- Analog Yearbook edited by Ben Bova.

- Capitol: The Worthing Chronicle by Orson Scott Card

- Captain Empirical by Sam Nicholson

- Projections by Stephen Robinett

- The Best of Astounding edited by Tony Lewis

- Maxwell’s Demons by Ben Bova

- A War of Shadows by Jack L. Chalker

- The Best of Analog edited by Ben Bova

- Hot Sleep: The Worthing Chronicle by Orson Scott Card

- The End of Summer: Science Fiction of the Fifties edited by Barry N. Malzberg and Bill Pronzini

- Class Six Climb by William E. Cochrane

I read (or in the case of Class Six Climb, attempted to read) all of them. I still own copies of most of the Analog Book books (Class Six Climb being the exception) and, counting this entry, I’ve reviewed five Analog Books. It wouldn’t be all that hard to polish the set off, except that I don’t particularly want to reread Card, and I don’t own the Cochrane. Surely the Cochrane couldn’t be as boring as I remember?

As those familiar with science fiction history will know, the reason an Astounding-Magazine-themed anthology was selected for an Analog-Magazine-named book line is because back around the beginning of the Space Age, Astounding was renamed Analog in an attempt to give it a more modern image. (It occurs to me I don’t know why Campbell settled on the word ‘Analog.’ If you know, please tell me in comments.)

Despite the anthology’s title, this isn’t intended as a collection that would cover Astounding’s whole publication run. The focus is on a specific decade in Astounding’s history, the golden age of the 1940s when John W. Campbell, Jr.’s Astounding lacked serious rivals and when Campbell had not drunk so deeply from the well of crank science.

While one might expect an anthology like this to helmed by someone revisiting their own personal golden age, Lewis was born in 1941. The stories he selected first appeared when he was between three and eight years of age. One wonders, then, where he encountered the tales2. My guesses:

● Three of the stories (“Cold War,” “Invariant,” and Thunder and Roses) were included in 1953’s Campbell-edited The Astounding Science Fiction Anthology.

● “Letter to a Phoenix” was widely anthologized. Lewis might well have seen it in Brown’s collection Angels and Spaceships.

● Ogre appeared in Wollheim’s Adventures on Other Planets.

● Piper’s story remained uncollected until this anthology. Perhaps the young and/or adult Lewis had access to a trove of old Astounding magazines.

Lewis also went to the trouble of tracking down and including the art that ran with the stories in their original run. Artists range from the new to me, such as Brush, Lester Elliott, and Willams, to well-known luminaries like Edd Cartier, whose name the text consistently misspells as “Cartler.” The art is always competent, if not remarkable. Cartier’s is probably the best.

“Best” is a risky word for a title, because it invites questions like “were these really the best?” and “if they were the best, what does it say that every other story Astounding published in the 1940s?” Well, best is a matter of personal taste. My take on this collection is that I found most of the stories (save the Neville) are at least memorable, if not always for their excellence.

Let’s look at the stories in detail.

“Introduction” (The Best of Astounding) • essay by Anthony R. Lewis

“Letter to a Phoenix” • (1949) • short story by Fredric Brown, interior artwork by Paul Orban

His life extended by a freak chance of atomic war, a long-lived human muses on what 180,000 years has taught him. Humanity seems doomed to endless cycles of rise and fall, but as he explains, this is not entirely bad.

Among the skills he learned: how to seduce and marry thousands and thousands of sixteen-year-olds, whom he then leaves when they are thirty. Ah, Classic SF values.

“Cold War” • (1949) • short story by Kris Neville, interior artwork by Brush

America’s orbiting atomic forts allow it to enforce global peace. There is a very carefully concealed risk involved, one that has thus far proved intractable.

This story is only as long as it is because the characters delay coming to the point as long as they can. The big twist recapitulates Heinlein’s “Blowups Happen.” I am not sure how this story in particular made the cut.

Ex Machina • [Gallegher (Henry Kuttner)] • (1948) • novelette by Henry Kuttner [as by Lewis Padgett], interior artwork by Edd Cartier

Gallegher sobers up to discover that for reasons he no longer remembers, his booze vanishes from the glass before he can consume it. It’s a bitter curse, particularly as he’d like to drink to forget his current problems, such as the murder charge he is facing.

Gallegher stories are all driven by three or four essential elements: drunk Gallegher is much smarter than sober Gallegher, sober Gallegher can never remember what he got up to while drunk, and he is not in the habit of leaving notes. The fourth element is that Joe, Gallegher’s vain robot, is always as unhelpful as possible. It’s a simple formula on which Kuttner enjoyed playing variations.

“Invariant” • (1953) • short story by John R. Pierce, interior artwork by Willams

Biological immortality has serious drawbacks. By the very nature of those drawbacks, the world’s sole immortal man is unconcerned by the inherent angst of his situation, which makes him an invaluable research tool.

Police Operation • [Paratime Police] • (1948) • novelette by H. Beam Piper, interior artwork by Edd Cartier

For thousands of years the Paratimers have quietly exploited the resources of less developed timelines, concealing their own existence and the fact that paratime travel is possible. A single careless Paratimer threatens the Paratime Secret by accidentally releasing a Venusian predator into an Earth without space travel. It’s up to Verkan Vall to find and eliminate the alien and provide a plausible cover story to the ignorant locals.

As this was published in the 1940s, when manly men shot animals with abandon, animals do not fare well in this story.

The Paratimers [3] are essentially parasitic in their relationship to other timelines, but as the story is told from their perspective, that detail gets passed over.

Ogre • (1944) • novelette by Clifford D. Simak, interior artwork by Frank Kramer

Interstellar traders from Earth are surprised to encounter a planet of intelligent plants. They waste little time working out how best to exploit their new trade partners. They only belatedly realize that the plants are just as cunning as the Earth folk. Just as the humans have plans for the plants, so too do the plants have bold ambitions for Earth.

In theory the plants are dreadfully alien. In practice, everyone in this story, human or alien, who gets lines speaks as if they were from Wisconsin. The exception is a plant who was exposed to dubious cultural materials from Earth. That one talks like a beatnik.

Thunder and Roses • (1947) • novelette by Theodore Sturgeon, interior artwork by Lester Elliot

America’s enemies surprised the USA with an overwhelming nuclear attack, an attack so successful that not only were almost all Americans killed or fatally irradiated, the after effects will surely doom almost every human in the northern hemisphere. Awaiting inevitable death, the handful of Americans still alive are forced to choose between doing nothing to punish their killers or unleashing America’s nuclear arsenal on the murderers and by so doing doom all life on the planet.

Thunder and Roses was selected for my Young People Read Old Science Fiction project. Reactions were mixed. It might seem to younger people that choosing not to snuff out all life on Earth is a no-brainer, but back in the 1940s that was not so clear (particularly in Astounding, whose editor seems to have considered death a solution for all of life’s ills).

1: The book I’m reviewing is not to be confused with James E. Gunn’s 1992 The Best of Astounding. The two anthologies do not overlap.

2: Lewis, the editor, is alive so one could also just ask him where he first encountered the stories in this collection … but where’s the fun in that?

3: Timelines keep dividing, so in fact there are a lot of variant Paratime home timelines: every possible version, in fact. How they don’t get in each other’s way is unclear. Why no possible Paratime culture has decided to reveal all is also not clear. Apparently, there are limits on what timelines can manifest.