Tower to the Sky

2300 AD

By Marc Miller, Frank Chadwick, Timothy B. Brown & Lester W. Smith

4 Oct, 2022

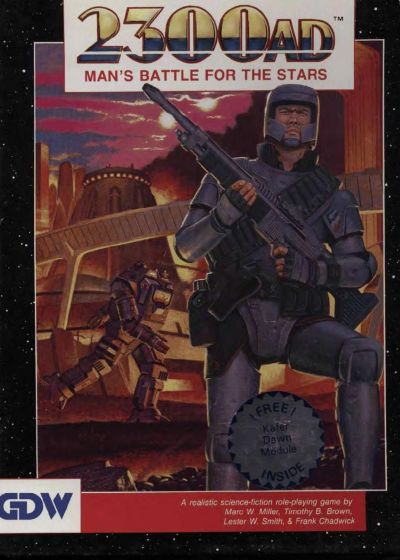

Marc W. Miller, Frank Chadwick, Timothy B. Brown, and Lester W. Smith’s1988 RPG 2300 AD1 is the second edition of a 1986 near-future hard-SF roleplaying game originally titled Traveller: 2300, put out by Game Designer Workshop. In addition to the rebranding, GDW substantially expanded second edition 2300 AD: whereas Traveller: 2300’s various manuals totaled 129 pages, 2300 AD’s manuals totaled 232. To sweeten the deal even more, GDW was willing to swap copies of Traveller: 2300 for copies of 2300 AD.

Inside the hefty and durable box2, gamers found:

One ten-sided die, two six-sided dice, a 96-page Adventurer’s Guide (player’s information), a 112-page Director’s Guide (game master’s information), a 32-page Play Aids book, and finally a striking full-color, poster-size Near Star Map, detailing the known stars within 50 light-years of the Sun. The poster is very pretty and I knew people who purchased the game just for the map.

2300 AD shared a setting with an earlier GDW. Not 1977’s Traveller, as many guessed from the original title, but 1984’s Twilight 20003.

Players of GDW’s rather gloomy post-nuclear war roleplaying game could take heart from 2300 AD, which revealed that terrestrial civilization not only survived the nuclear exchanges of the 1990s, but (after some time for recovery) flourished4. By 2300, humanity had spread to the nearer stars.

Aside from an admirable reluctance to use nuclear weapons on planetary surfaces, human civilization in 2300 is not notably more politically advanced than it was in 1988. Although the dancers had changed, the same dance continued, with alliances of nation-states competing for status, power, and resources. Although France is arguably the dominant state in 2300, recent setbacks (such as the long-delayed German reunification, attempt at which had helped trigger the Twilight War in 1995) suggested France is at best first among equals. The political situation has been complicated by contact with alien civilizations, some friendly (Pentapods), some hostile (Kafers), and others taking more ambiguous stances.

This setting had the advantage of offering players some novelty without too much unfamiliarity. The future geopolitical framework5 was recognizable; aside from advances required to facilitate interstellar travel, technological advances were likewise minimal (the imagined future computers in particular failed to keep up with real world developments). Novices would not have to invest too much time grasping all the implications of the game setting. While the aliens were very alien, they were also relegated to non-player-character status and only the gamemaster would know more about them.

Among the key assumptions of the game: while a faster-than-light drive exists, it is limited in range, which allows the designers to work with a manageable setting. Also, not all stars are created equal. Otherwise uninteresting stars can become valuable thanks to their location; players going from A to B are forced to visit systems they might otherwise ignore. As well, the limitations of the FTL drive meant that Near Space could be meaningfully divided into three main travel routes (or Arms), each of which offered its own unique adventure seeds.

Unsurprisingly, 2300 AD is very much a product of its time, which an informed viewer looking at the illustrations of firearms might guess to be “shortly after Aliens hit theatres.” Certain word choices have aged poorly: a modern game probably wouldn’t opt for “inferior” while discussing genes, even in the context of heritable disorders. The pronouns suggest that participants are men, although unlike many (most?) of the games of the period, neither the mechanics nor the illustrations suggest women are limited to support or decorative roles. They aren’t rewards or arm candy.

I was not and am still not crazy about the game mechanics. However, the background, especially that beautiful map and the accompanying star guide, were easily adapted to mechanics I did prefer. As well, while 2300 AD’s setting was far more constrained than Traveller’s, its hundreds of star systems make for a truly vast setting (five times the scale of SPI’s Universe). The option of an extended military campaign against the invading Kafer might have been the most obvious choice, but it was by no means the only option open to gamemasters and players. 2300 AD could support campaigns from military to merchant, from scientific to settler, or even more.

2300 AD is available here (DriveThru RPG) and here (Far Future Enterprises).

For more detail on what’s in the box:

All manuals were saddle-stitched, with simple paper covers. At the time I worried that they would not hold up to repeated use, but here we are, thirty-four years later, and no pages are missing. Which is more than I can say for the dice.

Adventurer’s Guide

These 96 pages detail how to generate characters. While the designers clearly prefer random generation, they also supply a points system. As is done in Traveller, characters are created (either through dice rolls or player choice) with personal and professional histories. Unlike Traveller, characters cannot die during character generation. Also unlike Traveller, career options aren’t skewed to military.

There is no index but there are two tables of contents: one sorted by page number and the other alphabetically.

Director’s Guide

This provides background information that will be known to the gamemaster and not to the players (at least at first). Of particular note: players don’t start out knowing much about the alien species in the game.

This section also lays out most of the game mechanics. The game designers seem to have felt that players didn’t need to be burdened with such knowledge. The players of 1988 would be delighted and surprised to find out just how fast and lethal combat could be.

Or perhaps not.

This section makes it clear that GDW viewed their games as cooperative efforts, not as a competition between gamemaster and players. To quote:

Satisfaction in refereeing should come from two different things. The first is the enjoyment of acting out diverse parts and painting word pictures of a multitude of settings. The second is a knack for enjoying other people’s pleasure, for seeing players have a good time in their adventures.

To put it mildly, not every company embraced this model of play, which is why certain adventures from rival RPG companies had a notably adversarial approach.

2300 AD exemplifies the great hazard of hard or hard-ish SF: science has marched on. Not only have stellar positions been adjusted in light of new data, but the world generation system has been outmoded by our greatly expanded knowledge of exoplanets6.

Near Star Map

This was a lavish, full-color, poster-size map of the known stars within 50 light-years of the Sun.

Play Aids

This was a 32-page book of aids, which provided 16 pages of forms, one 8‑page solitaire adventure, and most notably, a 9‑page catalog of star data, providing information about all of the stars listed on the map. This information was as up-to-date as was practical in 1988. These days such information is a judicious web search away, but in 1988 this was an invaluable resource.

I had an acquaintance who flipped through the star data (which is presented sorted by star name, not by the distance from the Sun) and commented immediately that the density of red dwarfs dropped with distance from the Sun. This is expected as dim red dwarfs are harder to spot than bright stars but I am still impressed by their ability to map tabular data into a three dimensional model.

1: Game credits: Mark W. Miller, Frank Chadwick, Timothy B. Brown, and Lester W. Smith.

2: My thirty-four-year-old box has proved quite durable.

3: Which had an unfortunate consequence: despite being set 300 years in the future, 2300AD was tied to a vision of the 1990s that became outdated a lot faster than anyone expected in 1988.

4: 2300 AD does make it clear things could have been much worse. One nearby alien race had starflight before their own nuclear war. By 2300, after many centuries of recovery, their lone remaining world has rediscovered the steam engine. Supplements revealed that other species were even more imprudent in their application of nuclear power and are now known only from archaeological relics and the occasional killbot.

5: Future predictions had been arrived at via a multiplayer “Great Game,” which simulated trends and conflicts of the next three centuries.

Players in the game were:

John Astell (Mexico, Romania, and India)

Rich Banner (Russia, Zimbabwe, and Canada)

Kevin Brown (Cuba, the Ukraine, and Australia).

Timothy B Brown (United Kingdom, Algeria, and Manchuria)

Larry Butz (Venezuela, Italy, Iran, and Angola)

John Harshman (France, Argentina, and Israel).

Dr David MacDonald (Military Government of the United States, Poland, and Canton)

Marc W Miller (Azania, Japan, Bolivia, and Egypt)

Matt Renner (Civilian Government of the United States, Sweden, and Nigeria)

Wayne Roth (Brazil, Spain, and Turkey)

Loren Wiseman (New America, Germany, and Indonesia)

Frank Chadwick (referee and kibbitzing player)

While Harshman clearly did well, points to Brown for earning the UK even second rank status, despite the handicap that the UK was virtually depopulated in the Twilight War.

Most nations were relegated to NPC status, which cannot have been helpful in the great struggle. I’ve never seen a copy of the Great Game’s rules (which of course would have constrained how history could have developed) but I can say that some of the outcomes, such as various African nations’ enthusiasm for becoming part of France, seem rather extraordinary.

6: To be honest, some of the system generation results seemed a bit odd, even in 1988