Under the Midnight Sun

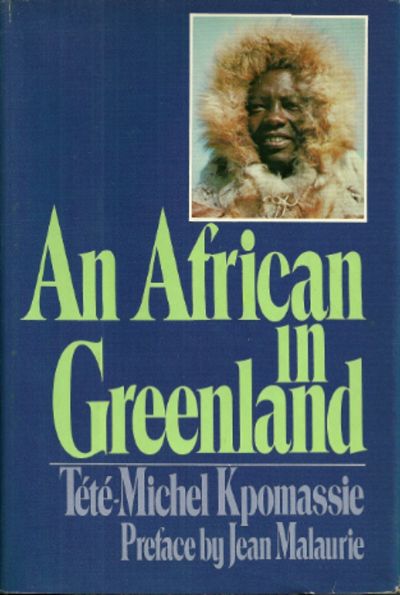

An African in Greenland

By Tété-Michel Kpomassie (Translated by James Kirkup)

15 Jun, 2022

Tété-Michel Kpomassie’s 1981 An African in Greenland is a memoir. Originally published in French, the 1983 English translation is by James Kirkup. The preface is by Jean Malaurie.

Born in 1941, Tété-Michel Kpomassie grew up in a traditional household in Togo. Startled by an inexplicably aggressive snake, he suffered a serious fall. Distrusting Western medicine, his father took young Tété-Michel to see a priestess, the price for whose treatment was that Tété-Michel Kpomassie should at a certain age come serve her religious organization in the sacred grove near Be.

Fate, in the form of Dr. Robert Gessain’s book The Eskimos from Greenland to Alaska, would intervene.

Enthralled by the glimpse of northern life the children’s book afforded him, the young African man resolved to one day travel from Togo to Greenland to see the wonders of the North for himself. Service in the sacred grove was therefore never to be.

Fearing that if he were to take a job that would pay well enough to finance his trip he would end up settling down in Africa, Tété-Michel instead held a number of less lucrative but unconfining jobs while pursuing a mail-order education. Thus, what might have taken him a couple of years of concerted effort (at the risk of never going1) became an episodic journey lasting eight years2. Ultimately, however, he succeeded.

Togolese and Greenlanders have the common experience of having been colonized by Europeans (Togo by Germany and France, Greenland by Denmark). While Togo became independent in 1960, Greenland in the mid-1960s is still firmly under the Danish thumb. The Danes are determined to modernize Greenland, an effort carried out without much feedback from the people whose lives are being transformed.

While Greenland’s cultures are very different from Togo’s, not only did Tété-Michel have some idea what awaited him, he was by virtue of his strategy for getting from Africa to the top of the world an experienced world traveler with considerable experience living in cultures different from his own.

Once he arrived in Greenland, however, he did not find the pristine arctic culture the book had led him to expect. He found a society heavily modified by extended contact with the Danes. If he wanted to achieve his original goal, he would have to travel north, where the Danish influence was less. Even then, success was not guaranteed.

~oOo~

Jean Malaurie’s preface points out that Kpomassie was not the first African to visit Greenland, although he appears to have been the first documented African to do so for the love of adventure and not because his employment required it. Malaurie dwells on various post-colonial issues raised by the account. Curiously, his discussion of the exploration of the far north does not appear to acknowledge that people lived there before Europeans explored the region.

Western readers should be aware that Greenland at this time took a very pragmatic view of animals, which seem to be generally sorted into “animals one hunts and eats” and “dogs,” who are neglected when not useful, worked hard when useful, and occasionally eaten3. Greenlanders do not have pets. The obverse is that dogs can in some circumstances see humans as food; Kpomassie notes several people killed and consumed by dogs.

Our traveler does not find a bucolic community living in an untouched Eden; what he encounters is a society with a thin margin of survival, a society where death is frequent. As well, meddling by far-off colonial masters often makes even this precarious existence even more precarious.

There are all too many travel books written by authors who are shocked by the scandalous ways of foreigners. Kpomassie is not that sort of writer. He does not expect Greenlanders to have the same customs as Togolese4. There would be no point to the trip if they did. While there are some moments of friction — he appreciates relaxed sexual mores when they redound to his benefit (he sleeps with the women he likes) and dislikes them when they don’t go his way (a woman leaves him for another) — on the whole he is happy to take the Greenlanders as they are. For example, he takes a distanced, almost anthropological view of local child-rearing customs.

An African in Greenland is an engaging read and I am happy that it seems to be still in print.

An African in Greenland is available here (Amazon US), here (Amazon Canada), here (Amazon UK), here (Barnes & Noble), here (Book Depository), and here (Chapters-Indigo) … although not in English. Yes, this is yet another example of a work by a POC widely available from other booksellers whose availability through Chapters-Indigo is limited.

1: Not least of the potential impediments to travel: the determination of his aunts to see him properly married off to a respectable Togolese woman (to be chosen by his aunts, naturally). One aunt suggested that he compose a love letter with the name of the recipient left blank, so that the aunt could fill in the name once she determined who it should be.

2: There is a Wikipedia entry for this book, which contradicts certain details in the account. I don’t understand how this happened, as Kpomassie’s account is quite explicit about how long it took him to get from Togo to Greenland.

3: One eyebrow-raising detail: generally speaking, Greenlanders didn’t eat dog unless hunting had been bad. They never ate dogs that have been killed for eating humans, due to the indirect cannibalism issue. However, they did eat dogs put down because they are rabid. Kpomassie is well aware of the potential contagion issue and at a loss to explain why the Greenlanders don’t catch rabies from their meals.

4: Kpomassie’s laissez-faire extends to other African cultures; he doesn’t expect his neighbors to live by Togolese customs.