Where the Green Rushes Grow

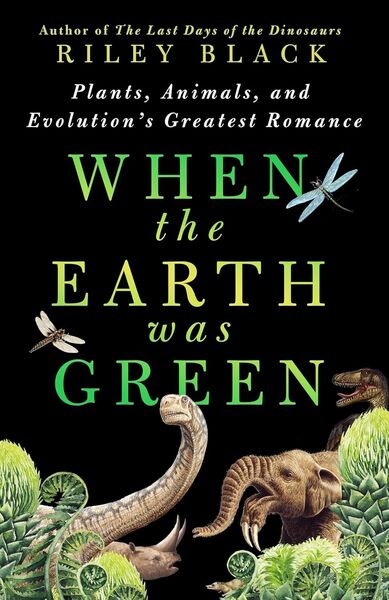

When The Earth Was Green

By Riley Black

9 Jan, 2025

Riley Black’s 2025 When the Earth Was Green is, as the subtitle proclaims, about plants, animals, and evolution’s greatest romance: the one between plants and animals.

Museums, television shows, and movies prefer to highlight the drama-friendly, toyetic megafauna. Dinosaurs are an excellent example. However, as Black points out, you can’t have the megafauna without the ecosystems of which they are the most flamboyant element. Dig down far enough and you reach photosynthesizing plants, the source for most of the energy flowing through living animals.

Plants, animals, and other lifeforms, and their environment, have complex relationships. Novel mutations, abiotic and biotic-driven environmental changes, abrupt catastrophes are forever altering the conditions in which living beings exist. Nothing stays the same for long.

To illustrate this fact, Black takes the reader on a speed-run through life’s history over the last 1.2 billion years, from an era when most life was unicellular, with a few exceptions like Bangiomorpha, to the current era, when most life is still unicellular but you can buy a Big Mac. Which, admittedly, is subpar from the cow’s perspective but very popular with humans. It’s a metaphor for the history of life! As would be cows developing toxic meat or forming a symbiotic relationship with deadly bacteria to discourage predators.

The book presents snapshots of Earth as it was in 1.2 billion years before present (BP), 425 million BP, 307 million BP, 220 million BP, 150 million BP, 125 million BP, 100 million BP, 60 million BP, 40 million BP, 34 million BP, 17 million BP, 9 million BP, 6 million BP, 3 million BP, and 15,000 BP. The thumbnail sketches of Earths long gone reveal how alien Earth once was.

~oOo~

Complaints first: if there’s an index, it is not in the ARC I received. Also, the book spends less time on the Azolla Event than I would prefer, in that I would have liked some coverage and there does not seem to be any. Oh, also the reviewing approaches I’ve developed for fiction and roleplaying games do not work well for non-fiction. Bummer, because I have some non-fiction I want to review in 2025.

Less a complaint and more an observation: there’s a bias towards recent events in the text. This is because, and I say this non-judgmentally, for almost all of its history Earth has been an extremely boring place for anyone interested in life who is not a microbiologist1.

By its nature, popular science texts face constraints on length, detail, and scientific vocabulary. Thus, while Green covers over a billion years, it does so in just three hundred pages. It uses scientific terminology with discretion; the terms have been judiciously selected for clarity.

It might be better to think of this as fifteen thematically related essays. Together, they add up to a flipbook-style animation of Earth’s rapidly evolving conditions. Earth has been a very alien world in the past and if one used a time-trebuchet to hurl graduate students into the past, most would perish immediately2. Black makes that clear3.

I am not the target market for this, having already read about the subject matter covered (thus the complaints about the Azolla event and the absence of Francevillian biota). I still enjoyed reading Black’s text and I would definitely recommend it to people curious about the recent history of life on Earth.

When the Earth Was Green is available for pre-order here (Amazon US), here (Amazon Canada), here (Amazon UK), here (Barnes & Noble), here (Chapters-Indigo), and here (Words Worth Books).

I did not find Green at Apple Books.

1: Come to think of it, the poor Ediacaran biota don’t get page time, either.

2: Graduate students who did not appear under two kilometers of ice, far out to sea, or standing on a Siberia-sized plain of molten basalt would still die.

3: Black also makes clear the role that susceptibility to fossilization has played in our knowledge of the past. If a life form left no trace in the fossil record, we can only know about it indirectly, if at all.