Why Such a Lonely Beach

A Christmas Carol

By Charles Dickens

26 Dec, 2019

Charles Dickens 1843’s A Christmas Carol. In Prose. Being a Ghost Story of Christmas is a standalone ghost story. Although the author failed to prosper in the science fiction and fantasy genres (in large part because they would not be codified until the following century), he enjoyed great success as a popular author.

Ebenezer Scrooge is living the dream: he has amassed an impressive fortune from which he derives a cold pleasure. He seems to have won at the game of life.

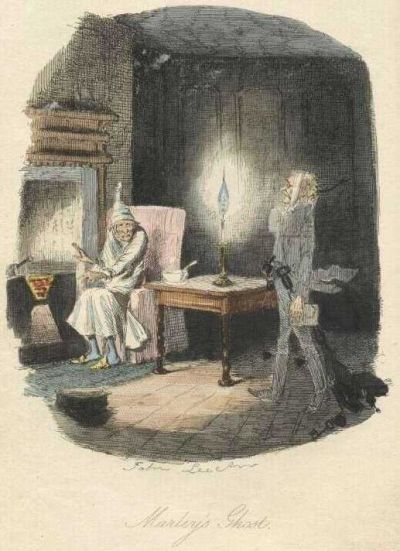

He discovers he has miscalculated the night that his long-dead business partner Jacob Marley visits him.

Marley is paying the cost of a life spent blindly pursuing wealth. Weighed down by a chain of greed he had forged in life, he is damned to an afterlife in which he is forced to witness the misery of those he could have helped in life but didn’t. Scrooge, Marley warns, is headed for the same fate. Scrooge may yet escape damnation, if he heeds the lessons taught by the three ghosts who will follow Marley.

The elderly miser is taken on a tour through time, visiting Christmases past (a time when he not the bitter, joyless man he is now), Christmas present (the sufferings his behavior cause those around him), and Christmas future (what will happen if he doesn’t change). The past is pleasant, the present is sad, the future is alarming.

But can he change?

~oOo~

I remember first reading this story in Trinidad in the fall of 1970, when I was nine. I hadn’t seen a TV or movie version … then. It must have impressed me, if I still remember when and where.

The tale seems oddly apposite in this era of great inequality. The callous rich are punished when they are confronted with the misfortunes they have caused, or ignored, and now cannot remedy.

The air was filled with phantoms, wandering hither and thither in restless haste, and moaning as they went. Every one of them wore chains like Marley’s Ghost; some few (they might be guilty governments) were linked together; none were free. Many had been personally known to Scrooge in their lives. He had been quite familiar with one old ghost, in a white waistcoat, with a monstrous iron safe attached to its ankle, who cried piteously at being unable to assist a wretched woman with an infant, whom it saw below, upon a door-step. The misery with them all was, clearly, that they sought to interfere, for good, in human matters, and had lost the power for ever.

Why the dead rich belatedly feel empathy is unclear. Nor is it clear why Scrooge in particular is granted the boon of knowledge before he dies and thus given a change to do good for a change. Perhaps it is because a few visions are sufficient to convert him from miser to philanthropist overnight. He was open to change, as odd as that might seem.

I just realized while writing this that A Christmas Carol is Dickens telling himself that he CAN change society by writing about the sufferings of the poor. If only the rich knew what it was like at the bottom of the heap (as Dickens well knew) they would change. It’s a pep talk from Dickens to Dickens: keep on keepin’ on, dude; you can convince the thoughtless rich!

He had a fair bit of success. Little Dorrit helped change the laws re imprisonment for debt. Oliver Twist pushed for change in the Poor Laws. If you’re interested in his effect on the Victorian conscience, you might like to read this essay.

But perhaps converting the rich is a Sisyphean labor. If we look at modern-day England, we see Scrooges rampant. That’s too bad for England’s poor. But it’s good for the continued relevance of Dicken’s little tale, which assures us that oligarchs can change. Which I suppose is one of Death’s necessary lies1. No point in pushing for reform unless one thinks it is possible.

A Christmas Carol is available on Gutenberg.

1: