Never There On Time

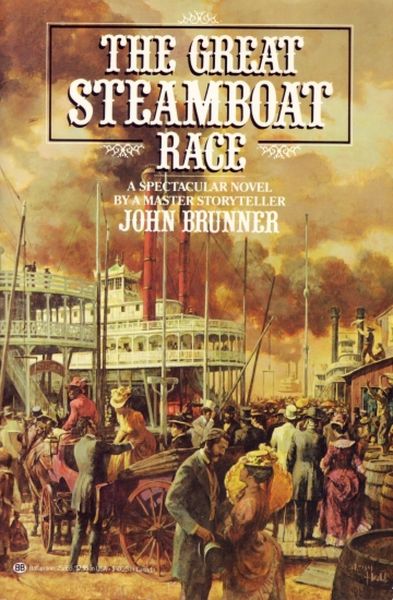

The Great Steamboat Race

By John Brunner

30 Jul, 2024

John Brunner’s 1983 The Great Steamboat Race is a stand-alone historical novel.

Despite the advanced technology and skilled pilots of the 1870s, the Mississippi was still an often-dangerous river on which to operate steamboats. Prudent men would not exacerbate the hazards with dubious endeavors such as races.

Prudence is a virtue more lauded than practiced. Which brings us to the matter of the steamboats Atchafalaya and Nonpareil.

Hosea Drew’s brother Jacob ran up a hundred thousand dollars of debt before he died of the pox. Hosea has painstakingly paid back every dollar. To do so, he scrimped on maintaining his steamboat. Now that steamboat has been rightfully condemned as too unsafe to operate. Hosea has insufficient funds to replace it.

Enter Langston Barber. Barber has a dubious reputation but no lack of funds, not least because he was one of Jacob’s creditors. Recognizing that Drew is one of the best riverboat men on the Mississippi, Barber provides the funds for Drew’s new boat, called (like the one before it), Atchafalaya.

Miles Parbury was arguably Drew’s equal. An encounter during the American Civil War with Union soldiers turned Parbury’s steamboat Nonpareil into flaming wreckage. Parbury survived… at the cost of his eyesight.

Enter the mysterious Hamish Gordon. Believing Parbury as sharp as ever, Gordon provides the funds to turn Parbury’s design for a cutting-edge steamboat into reality. Result, a new Nonpareil, more modern and much faster than its doomed predecessor.

Which is faster, Atchafalaya and Nonpareil? A race would not only decide the issue; it would enrich bookies and (a few) gamblers. It would sell newspapers! A race would be so clearly beneficial to society that the fact that neither Drew nor Parbury want a race is irrelevant. Too much money is riding on the outcome to let the pair prevent what everyone else agrees is inevitable.

Filled to the gunnels with a vast cast of characters, each person’s fate entangled with the outcome of the race, the two steamboats set off on the great steamboat race. Who will win? More importantly, given the lengths to which gamblers will go to secure victory, who will survive?

~oOo~

Blame John Jakes.

By the early 1970s John Brunner was in something of a financial trap. To maintain the income he needed through science fiction and fantasy sales, he had to produce so many works that none of them could be carefully polished. When he did take the time to create masterpieces like Stand on Zanzibar, The Jagged Orbit, The Sheep Look Up, and The Shockwave Rider, critical accolades abounded but sales were not commensurate with the extra effort required.

Enter John Jakes. Jakes was a speculative fiction writer, a member of Lin Carter’s Swordsmen and Sorcerers’ Guild of America. As to the quality of Jakes’ SFF books, one can confidently say they contained words in a row. In the early 1970s, Jakes ventured into historical fiction with the Kent Family Chronicles. The Kent Family Chronicles were fantastically successful, reportedly selling 55 million copies. To Brunner, in desperate need of a more viable model, swerving to historical novels made sense.

What followed was a five-year silence from Brunner as he worked on The Great Steamboat Race. Between 1975’s The Shockwave Rider and 1980’s The Infinitive of Go, no Brunner novels appeared. The Great Steamboat Race finally appeared in February of 19831… to a resounding lack of sales. Brunner’s gamble on a mid-career genre change was a disastrous misstep.

What went wrong? I’ve read that Brunner blamed George R. R. Martin’s October 1982 Fevre Dream. Fevre Dream also featured Mississippi steamboats. It even referenced the same race between the Natchez and the Robert E. Lee that inspired Brunner’s (very different) race between Atchafalaya and Nonpareil. It’s another example of two authors independently hitting on the same idea at the same time. I don’t think Fevre Dream can be blamed for The Great Steamboat Race’s woes2.

It’s possible that The Great Steamboat Race was its own worst enemy. The novel clocks in at 568 pages, in large part because Brunner’s cast is so large and their intertwined tragic backstories so detailed that it takes almost half the book to get everyone in position at the starting line. The pacing in the first two hundred pages is… let’s say deliberate. Certainly not as breakneck as the race that ensues. That said, it’s not as if Shogun had been in any hurry to reach the end of the plot. I know little about historical novel conventions and it could well be that what seems a bit slow to someone used to authors cramming whole space opera spectacles into 168 pages was perfectly fine to historical novel fans.

For my money, the fault was due to Brunner’s painstaking research and writing process, which let to extremely unfortunate timing. Judging by the Great Silence, Brunner began work on The Great Steamboat Race in 1975 or 1976. It didn’t see print until 1983, by which time, to quote noted author Walter Jon Williams, “historical fiction was as dead as a frozen mackerel […]”. Perhaps if Brunner had written a little faster, if Ballantine had produced a shiny hardcover3 in 1980 instead of a trade in 1983, we’d be musing that the noted historical best-seller novelist John Brunner was once a well-regarded science fiction author.

All that said, I enjoyed The Great Steamboat Race when I first read it. Having tracked down a used copy — it was easy to find a very reasonably priced used copy4—I thought it a perfectly reasonable read this time through. I hate the effect this book’s failure to launch had in Brunner’s career, but I don’t hate the book itself.

The Great Steamboat Race, having had one trade-paperback edition forty-one years ago, is very sincerely out of print.

1: At least, that’s the release date the ISFDB has for it. February seems like an odd month to release what was intended to be Brunner’s breakthrough into historical fiction.

2: It’s probably a good idea to explain that at this point in their careers, George R. R. Martin was a promising midlist SFF author for whom Fevre Dream was his third novel, whereas John Brunner was the established big-name author.

3: I don’t know if it was a mark of faith in the novel that Ballantine released it as a trade or a lack of faith that it was not a hardcover. Previous Brunner novels from Ballantine/Del Rey appear to have been mass market paperbacks.

I can say that while the paper quality and binding were not as terrible as Baronet trade books or Lancer mass market paperbacks, they aren’t great.

4: My copy came with this bookmark.

The coupon was between pages 124 and 125. I don’t know if that’s significant or just where the bookmark was tucked after the reader read the entire book cover to cover.