Though Cowards Flinch and Traitors Sneer

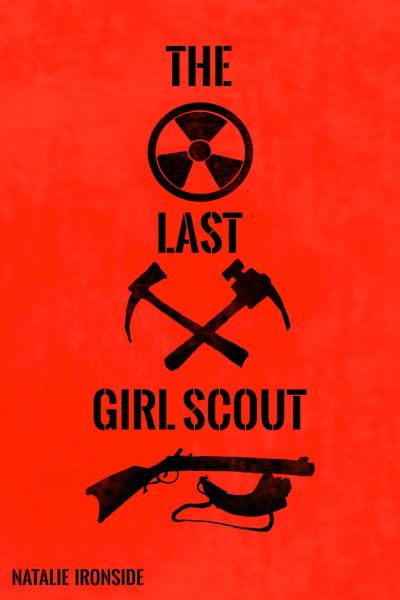

The Last Girl Scout

By Natalie Ironside

15 Oct, 2020

Natalie Ironside’s 2020 The Last Girl Scout is a standalone post-apocalypse adventure.

After the war, what was once the United States is a patchwork of pocket nations interspersed with radioactive wastelands overrun by zombie hordes. In the middle of one such wasteland lies an enigmatic structure known as the Citadel. The Ashland Confederated Republic decides to seize it. Result? Two companies march into the wasteland. Two survivors straggle back.

Common sense would suggest that it would be wise to leave the Citadel alone. But when Ashland learns that another pocket nation is targeting the Citadel, it does what it should have done at first: send a scouting mission into the wasteland. Commissar Magnolia “Mags” Blackadder very reluctantly agrees to join the mission.

Ashland does its socialist best to provide its people with decent lives. In contrast, the neighbouring Blackland New Republic is run by white supremacist fundies. Crushing that damn socialist Ashland is very high on the Blackland to-do list. What role the Citadel plays in Blackland’s plans is unknown, but the threat that it will be a nasty one is enough to justify what is almost certainly a suicide mission.

The scouting party consists of: Professor Jackson McCreedy and Connor Turlogh, the two survivors of the earlier military fiasco, Mags herself, and a Blacklander defector, Julia “Jules” Binachi, with whom Mags is immediately smitten.

The Citadel is located in a barely habitable zone between the former New York (now glassed and radioactive) and the former Washington DC (now glassed and radioactive). The Citadel has been untouched by the war. It is crammed with pre-war weapons (nuclear, biological, what have you). It is inhabited by centuries-old “hunters” (the polite 23rd century term for draculas). The hunters are the result of a misguided effort to produce super-soldiers; they are super-strong, hard to kill, and thanks to their extended life-spans, extremely good at holding on to old grudges.

If Blackland could seize the Citadel, it could wipe out Ashland. It is up to Mags and her fellow scouts to survive the wasteland, infiltrate the Citadel, and destroy the contents. The odds would seem to be against them.

Even if they succeed, they cannot prevent the next war. With or without the Citadel’s weapons, Blackland will attack Ashland.

[break]

It happens that both Mags and Jules are trans. You might wonder how well a post-apocalyptic white-supremacist Christianist nation treats trans people and the answer is “not well.”

I know, it’s weird that there are so many parallels between this book and Hiero’s Journey, recently reviewed. There’s no war moose in this novel, but there are Canadians (albeit almost entirely off-stage), zombies, and vampires. Odd how often book reviewers discover unintentional synchronicities. I can’t even blame the zeitgeist because the two books were published half a century apart.

Now let me kvetch. The timescale in this novel doesn’t make sense. It’s 2259, but the ruins of pre-war department stores are still recognizable. Both the Blacklanders and Ashlanders are using contemporary guns: AR10s for Team Evil and AKs for Ashland. Either Blackland and Ashland have access to some impressively Ragnarok-proofed arsenals (not impossible) or there has been no innovation in firearms for a quarter of a millennium. While one could understand why the Ashlanders would backburner firearm R&D in favour of more utilitarian projects1, one would suppose that the Blacklanders would be keen on finding new ways to kill people.

Cultural references are for the most part to people, events, and political factions that would be familiar to 20th century folk. Surely, even if the outlines of the politics of tomorrow were rotoscoped from today’s or yesterday’s political conflicts, the folks in the future would be using new terms?

The book might make better sense if it were set in, oh, 2060 or even 2040, a generation or two after near-future conflict.

Now it may seem from the synopsis that Ashland is an all-good Team White hat and Blackland is the all-bad Team Black hat. Not quite.

Ashland’s goals are lofty and its methods ostentatiously politically correct, but it has the usual sprinkling of self-serving jerks of the sort familiar to anyone who has moved in lefty circles2. As for Blackland, nothing it espouses is good, but many citizens aren’t evil, just scared. The consequences of dissent are nasty3.

Which is not to say that the two sides are equally bad. If you dissent in Ashland, what you risk is internal exile or worse, having your friends form an ad hoc people’s committee to encourage you to process your feeeeeeeelings in a supportive and ideologically sound manner4. Over in Blackland, citizens who aren’t gung-ho for the regime are simply shot. Or worse. Guess where you would want to live.

Ashland knows that many Blacklanders are just keeping their heads down and, to their credit, they aren’t preaching a crusade against evil Blacklanders. Instead, Ashland does its best to encourage defectors (who must then forswear their old beliefs and commit to Ashland). These policies seem to work fairly well [5]. No doubt it helps that the author is on Ashland’s side. It’s certainly an interesting change of pace from the many SFF novels in which the bad guys must be exterminated root and branch.

This seems like an appropriate moment to note that the author’s bio says that the author was

a soldier, a (former) member of the white nationalist movement, and a soil analyst in addition to being an award-winning author of speculative fiction.

One can see the personal development arc that has sparked the novel’s plot.

Post-apocalyptic right-wing-leaning MilSF is fairly common. Far left post-apocalyptic MilSF is rather less so. This particular example is uneven—it could have used a pass from an editor willing to trample repetitive phrasing—but the novelty of the political perspective was enough to keep me reading. Plus, the prospect of the usual post-apoc adventure reader picking this up has considerable comedic potential.

The Last Girl Scoutis available here (Amazon US), here (Amazon Canada), here (Amazon UK), but not from other book sellers.

1: It is a plot point that Ashland funds a lot of research into rehabilitating contaminated land and making better use of the land they have.

2: Speaking of unanticipated synchronicities, Ashland suffered an attempted factional coup in its recent past that is surprisingly similar to the process by which UWaterloo’s student paper, The Chevron, was taken over by doctrinaire baby Stalinists back in the 1970s.

3: In Blackland, being less than enthusiastic about the regime is treason. Traitors are executed. Excessive enthusiasm is lauded. The result is that Blackland’s guiding military philosophy is less Sun Tzu and more Leeroy Jenkins. This is not entirely to their benefit.

4: Ashlanders reserve the touchy-feeling stuff for each other. Blacklanders who don’t surrender generally don’t live long. Be assured there is enough of shooting and stabbing to keep post-apocalyptic fiction fans happy.

4: Except in the case of one high-ranking Blacklander defector, who decides that they’d rather be summarily executed by the Ashlanders than admit error.